It’s a scene you’ve experienced if you have children. Your young daughter screams out in the night. You rush to her side and find her semi-awake, still trapped inside a nightmare, and crying out, “Daddy! There’s a monster chasing me!” What do you say? Do you say, “Run faster, Hunny, faster!” or perhaps “Hide behind a tree or under the staircase!”? Do you confirm the reality of her nightmare this way? Or perhaps you let her nightmare define you as well and pace the floor feeling as desperately forsaken as she does.

It’s a scene you’ve experienced if you have children. Your young daughter screams out in the night. You rush to her side and find her semi-awake, still trapped inside a nightmare, and crying out, “Daddy! There’s a monster chasing me!” What do you say? Do you say, “Run faster, Hunny, faster!” or perhaps “Hide behind a tree or under the staircase!”? Do you confirm the reality of her nightmare this way? Or perhaps you let her nightmare define you as well and pace the floor feeling as desperately forsaken as she does.

Here’s what you do. You hold her in your arms and say, “It’s alright my love, Daddy is here! Don’t be afraid; Daddy’s here,” and you gently rock her in your arms until her reality conforms to your reality, that is, until your reality defines her reality by putting the lie to her nightmare. You save her from her nightmare by exposing it as false, not by letting it falsify in you the truth that contradicts the nightmare. That’s a rough analogy, we believe, for how it is that God awakens us from our nightmare through incarnate suffering.

“But this doesn’t require incarnation,” you say. “To save us,” you insist, “God didn’t speak into our world from outside.” Quite right. To save us from our nightmare, God enters our nightmare. Or if we’re talking about my daughter who is stuck in a bad dream, then I enter her nightmare to rescue her. So let’s extend our analogy of the dream to include this. How might some such model be possible and maintain anything like an Orthodox, Chalcedonian Christology?

Lucid dreaming is a well-studied and documented phenomenon. A lucid dream is a dream you have in which you’re aware that you’re dreaming but you don’t awaken from the dream, and the dreamer even has a measure of control over her participation in the dream. Lucid dreams can be extremely vivid. Just because the dreamer is aware she’s dreaming doesn’t empty the dream-world of its vividness or the experienced, first-person perspective of the dreamer from within the dream. Lucid dreaming has even been used to treat persons who suffer from nightmares. It’s not yet known how it is that the technique of lucid dreaming and lucidity exercises address the problem of repetitive nightmares, but it has been documented to work.

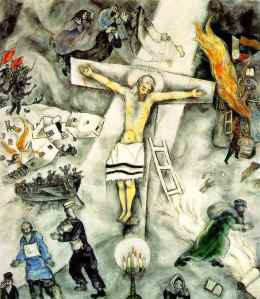

Analogy time. Let us offer lucid dreaming as an analogy or model for understanding an Orthodox two-minds Christology. Tom Morris described this back in 1986 in The Logic of God Incarnate. In this lucid dream analogy of the Incarnation, the dreamer (the divine Son/Logos) is aware — outside of his own incarnate participation in the dream — that he’s having this dream. That places him both outside and inside the dream (of creation). You might say he transcends the dream. There’s more to ‘him’ than there is to ‘him-in-the-dream’. He’s in the dream, he’s just not exhausted by it. Applied to my daughter, I choose to enter incarnationally into her nightmare. I’m in the bedroom holding her in my contented, peaceful embrace and I’m also in her dream being crucified by monsters.

But what about that cry of dereliction? “Why? Why have you forsaken me?” Surely there’s no way I could be on the Cross feeling forsaken, inside the dream asking this particular question, and yet also be outside this cry holding it all in existence, sustaining it in triune joy and contentment as its dreamer. Surely with this cry of dereliction the knife is plunged into God’s heart and there’s no transcendent space for God to hide from it.

But what about that cry of dereliction? “Why? Why have you forsaken me?” Surely there’s no way I could be on the Cross feeling forsaken, inside the dream asking this particular question, and yet also be outside this cry holding it all in existence, sustaining it in triune joy and contentment as its dreamer. Surely with this cry of dereliction the knife is plunged into God’s heart and there’s no transcendent space for God to hide from it.

To this we reply, Why think that? In lucid dreams the dreamer transcends the dreamt. The dreamt does not, within the constraints of the dream, transcend the dreamer. This is just an analogy, of course, but it does what analogies are supposed to do, and that is to make claims conceivable. We are able to conceive of the Son’s experiencing the Cross and also having an experience outside the Cross. The Son was born, named Jesus, ate, got tired, became hungry, and finally was hung on the Cross. But the Son need not be reduced to this finite history. He is in the nightmare, but the nightmare does not exhaust who and what he is.

Even when the epistemic distance (to borrow Hick’s term) inherent to the context of the nightmare is increased so greatly and the absence of the Father’s felt presence presses him so intently to despair, to sin, to embrace the nightmare as the truest thing about who he is, Jesus refuses. He refuses to step outside his relationship to his Father as the Son. As far as Jesus is concerned, he is still his Father’s son, and he self-identifies as the Father’s son all the way though the Cross until he dies with “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.”

We are meant to view this, to see it, to see human nature put to the test again, to again entertain those doubts born of the epistemic distance inherent to our finitude (as in the Garden) or born of suffering, to wonder and question again, to be in a context void of every evidence of the Father’s love and presence but – this time – love in return. In Christ, humanity trusts in the face of all evidence to despair. There is only unquestioning obedience and trust: “I am my Father’s Son right here, right now, on this Cross, no matter what this nightmare says I am.” Thus it is in Christ’s filial self-identification on the Cross that the absence and rejection of God are revealed to be myths of a false and despairing perception, not the truth that saves us.

Question. By whom is Christ empowered not to step outside his identity as the Father’s Son? If the Father has decided, as some say, to absolutely abandon his Son on the Cross thus withdrawing from him every spiritual resource, by what means was Jesus then empowered to self-identify as his Father’s Son, so contrary to his pain? By the Spirit of God of course. If the Son is forsaken by the Father as absolutely as some think, apparently the Spirit refused to go along with the program, for the Spirit is present empowering Jesus on the Cross to self-identify as Son, as beloved and begotten of his Father, within the pain of his circumstances and contrary to them. The Spirit empowers Jesus to reject that interpretation of his circumstance which concludes he is no longer beloved of his Father. THAT is how his coming into our nightmare sets us free. Christ’s transcendent choice to self-identify as the Father’s Son (and thus to identify God as his Father) on the Cross tells us that the nightmare is not the truth about us. We are not rejected. We couldn’t possibly be. To “wake up” from the nightmare of our sinful misrelating and despair is just to perceive that nothing about the nightmares that define our despair is ultimately true about us.

Welcome to the truth of apatheia.

(On the ‘Cry of Dereliction’ see Not what you suppose and A cry of dereliction?.)

I interpret Jesus’ cry of pain (My God, why have you forsaken me?) as a true statement of Jesus’ experience. Jesus could not feel His Father’s presence, hear His Father’s voice… In the same manner, the Father could not make His presence manifest to His Son, not because of any inability of the Father, but because of the Son’s human inability to feel the Father’s presence. Thus, Jesus was truly separated from the Father, even though the Father never actually left him. And Jesus, though He could not feel His Father’s presence, He never stopped being faithful in His love for the Father. And the Holy Spirit was there also, keeping Jesus focused on the joy set before Him and giving Jesus strength to remain faithful. Therefore, though the separation from the Father that Jesus experienced was real experientially, the love that Father, Son and Holy Spirit have for each other (in their subjective, individual and passionate resolution) kept the Trinity whole and holy. God never stopped being love; therefore, God never stopped being God.

LikeLike

That’s virtually my view as well, Nelson. I hope we didn’t lead you to think that we thought Jesus really did feel the goodness and joy of his Father’s presence on the Cross. He didn’t experience that. BUT…and this is where we might disagree…though JESUS did not experience the fullness of the Father’s presence and love while he was on the Cross, THE SON did continue to experience the Father’s favor, for the incarnation is “one PERSON, two NATURES.” There is more to the SON than his incarnation as JESUS. It’s incarnation by addition, not subtraction. So there’s no question that JESUS suffers the loss of experienced joy with his Father as a human being on the Cross. This just doesn’t have to mean the SON/LOGOS is reduced without remainder to the experience of the Cross.

What do you think?

LikeLike

If I understand you correctly, your saying the the Son/Logos did not experienced the cross; just the human Jesus did. If that is what your saying, I think that your making a distinction that Scripture does not make. I believe that you subscribe to Chalcedonian christology. I find the Chalcedonian formula inadequate, because it is contradictory (http://anglicansonline.org/basics/chalcedon.html).

I believe that the Son/Logos became man. I believe the Son/Logos became lower than the angels (Heb. 1:9, NIV) for a little while. I do not believe God has apatheia. I believe God has passion. I believe that is what love is: the divine passion born out of the heart of God.

I’m just glad that even if I don’t get how God became man, I can still trust in Him, because God is love and not theology.

LikeLike

Nelson: If I understand you correctly, your saying the Son/Logos did not experience the cross, just the human Jesus did.

Tom: I hope Dwayne’s reply helped. We’re not saying that the Son/Logos did not experience the Cross and that only the human Jesus did. We’re saying the human Jesus IS the Son/Logos, and Jesus’ experiences are the experience of the Son/Logos, BUT that there is more to the Son that Jesus’ human experience.

Nelson: I find the Chalcedonian formula inadequate, because it is contradictory (http://anglicansonline.org/basics/chalcedon.html).

Tom: That would definitely be a point of disagreement between us then.

Nelson: I believe that the Son/Logos became man. I believe the Son/Logos became lower than the angels (Heb. 1:9, NIV) for a little while.

Tom: So do we and so do those who adhere to Chalcedon. We just believe that in experiencing birth, hunger, life on earth, and death, the same Son/Logos didn’t have to stop experiencing triune fullness and joy as God.

Nelson: I do not believe God has apatheia. I believe God has passion. I believe that is what love is: the divine passion born out of the heart of God.

Tom: apatheia is not the absence of passion (depending on what you think ‘passion’ is; it sounds like you think it means something like ‘felt experience’ or ‘the experienced quality of life’). You might want to rethink what you think apatheia is, because it doesn’t require us to view God as a cosmic stuffed shirt, so to speak.

Nelson: I’m just glad that even if I don’t get how God became man, I can still trust in Him, because God is love and not theology.

Tom: Certainly. But saying “I can trust God because God is love” is theology.

LikeLike

Nelson, I’d be interested to know which part of Chalcedon to you believe is contradictory? Here it is:

We all we teach men to acknowledge:

– one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ,

– at once complete in Godhead and complete in manhood,

– truly God and truly man,

– consisting also of a reasonable soul and body,

– of one substance with the Father as regards his Godhead,

– and at the same time of one substance with us as regards his manhood,

– like us in all respects apart from sin,

– as regards his Godhead, begotten of the Father before the ages,

– as regards his manhood begotten, for us men and for our salvation, of Mary the Virgin, the Godbearer,

– [he is] one and the same Christ, Son, Lord, Only-begotten,

– recognized in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation,

– the distinction of natures being in no way annulled by the union,

– but rather the characteristics of each nature being preserved and coming together to form one person,

– not as parted or separated into two persons,

– but one and the same Son and Only-begotten God the Word, Lord Jesus Christ.

Where’s the contradiction?

LikeLike

I want to make sure that it’s not being perceived that we are saying the the Uncreated Logos/Word of God the Father has an identity separate from Jesus of Nazareth post-Incarnation. That’s not what we are saying. We are saying that the entire subjectivity of Jesus is directly attributable to the Word/Logos such that the Word/Logos is the one and only personal subject/agent of all of the creaturely experience of Jesus of Nazareth. No other person–including God the Father or the Holy Spirit–personally experiences of the creaturely reality of Jesus. This is how we can say that:

1) “true God from true God” actually experienced birth through Mary and death in crucifixion: God was born and died.

2) the Word/Logos suffered death as Jesus…but it was impossible for death to hold him as Jesus.

3) Jesus truly reveals who God is.

4) there is “more” to the Word/Logos than Jesus, but *never* less.

For clarification.

LikeLike

Nelson,

This is the question that we ask to show some things…

“When the Son/Word became a human zygote in the womb of Mary, did He cease sustaining all Creation by the power of his word? (Heb 1:3)”

If he did, then that implies that the Father can sustain Creation without his Word…and that’s tritheism.

If he did not, then you have to think about whether or not a human zygote has the innate power to sustain all Creation. If you don’t think it does, then one must posit that the Son/Word *transcends, yet includes” being a zygote in Mary’s womb….and that “transcendence” is how the Son/Word continues his creative role as the Uncreated Word of God the Father.

Make sense?

LikeLike

@tgbelt:

“but rather the characteristics of each nature being preserved and coming together to form one person and subsistence” (Translation from Bettenson, Henry. Documents of the Christian Church. Oxford Univ. Press, 1947, p. 73) In the translation you used, the word subsistence was missing.

This clause seems to suggest that in Jesus (God in flesh), opposing characteristics of what the formula calls the two natures (divinity and humanity) coexist at once[*]. How can contradictory characteristics be united in one person “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation” and yet “the distinction of the natures [is] not annulled by the union”. How is divine infiniteness preserved while humanity’s limitations are acquired? To be fair, the formula does not mention what divine characteristics remain during the incarnation. But if the idea is that in His incarnation the Son took the form/nature of a human, then those divine characteristics that are not compatible with human nature had to be put aside/stripped away/emptied. The Chalcedonian formula makes it seem like in His incarnation, the Logos acquired human form/nature without letting go of any of the characteristics of His divine form/nature. It seems to suggest that the Almighty became weak without stopping being almighty; that the Omnipresent became a historical individual in first century Palestine without stopping to be in all places at the same time.

[* I am assuming that “at once” refers to Jesus’ earthly ministry. If “at once” refers to the presently exalted and glorified Jesus Christ, then I must concede that then -and only then- does Jesus possess everything. Because, in the resurrection and ascension/exaltation of Jesus Christ by the Father, Jesus reconciled the divine and the human, and received everything from the Father (kingdom, authority and power).]

I do not claim to understand the Incarnation. I believe it is a paradox. But to come up with a formula that purports to explain the Incarnation and call those who disagree with it “unorthodox” (or worst, heretics) is a little arrogant. Plus, I don’t like that in the original Greek formula, the term hupostasis (nature, substance, reality) was used to describe/define divinity and humanity, instead of keeping the biblical term morphē (form, shape, and in a figurative sense, nature). (Strong’s concordance 3444 and 5287).

I believe that in the Incarnation, the Logos emptied Himself of divine characteristics incompatible with the possession of humanity, but kept those attributes that were possible to translate into humanity: His character, His holiness, His love. Thus, I believe that Jesus is the incarnate love of God, because the divine love is what Jesus came to express, to live out, to flesh out. And love is the fullness of God. God is love.

That is my conception of the Incarnation.

—————————————————–

@yieldedone:

Where does it say in Scripture that the Father cannot sustain His Creation? In Mathew 5:45 it says that the Father causes the sunrise and sends down rain.

And in John 5:19,20 it says that the Son does what the Father does and nothing more. Now, these verses could be referring to the Incarnate Son only. However, if the Son is the image of the Father, then what Jesus says in these verses could apply eternally, because the image reflects what the source does. Everything is done in love, though.

LikeLike

Nelson, thanks for sharing. Appreciate it. Your views are standard kenotic beliefs, and Greg’s expressed them in almost identical language. So you’re in good company.

Couple of ideas (and then we may just agree to disagree):

1) I left the word “subsistence” off of the phrase “coming together to form on person and subsistence” just to keep the text simple for discussion’s sake. Nothing’s lost, since ‘subsistence’ simply repeats by way of clarification what is intended by ‘person’. They’re the same.

2) I’m a bit confused by your accepting the incarnation as a “paradox” which you “cannot understand” but then criticizing Chalcedon because it’s “contradictory” and can’t be rationally understood. You obviously don’t mind embracing some paradoxes you can’t understand. So how do you choose one impossible-to-understand paradox over another?

3) In the hypostatic union it’s not claimed that the divine attributes of the Son be instantiated in terms of his human nature (and so why isn’t Jesus’ human mind omniscient? Why isn’t Jesus’s body omnipresent, etc). It’s only claimed that they are instantiated by the person of the Son with respect to his divine nature. Is this ‘one person, two natures’ Christology conceivable? Well, you’ve already admitted that your version of the incarnation (a kenotic understanding) is a paradox you can’t understand. So you shouldn’t have qualms about paradox or the inability to comprehend per se, right? Actually, we think the lucid dreaming analogy at least makes the Orthodox ‘one person/two natures’ view conceivably plausible. But no kenoticist has offered an account of where the eternal Logos even is as a person when all there is to him is a 2-celled zygote in Mary’s womb. When we’re done complaining about the contradictions in Chalcedon, can we move over to those of your kenoticism?

4) About the arrogance of believing this or that view of God to be heretical, let me ask you Nelson, do you admit to the possibility of any heretic beliefs at all? Are there such beliefs? If so, is it always arrogant to point them out? I mean, is it ever possible in your opinion to identify heresy without being arrogant? If so, then what makes our identification of kenotic Christologies as inherently heretical seem arrogant to you? Is it always arrogant to identify heresy? Is it possible to identify heresy humbly?

5) You ask, “How is divine infiniteness preserved while humanity’s limitations are acquired?” By hypostatic union, by the transcendence of the limited by the unlimited. The Son/Logos may be omnipresent and yet personally present in the limited constraints of Jesus. The integrity of the Son’s humanity doesn’t metaphysically require that Son be “reduced without remainder” to those constraints.

6) Most importantly, Nelson, you say, “…the Logos emptied Himself of divine characteristics incompatible with the possession of humanity but kept those attributes that were possible to translate into humanity: His character, His holiness, His love.” Good. Those three divine attributes (character, holiness, and love) only exist (unless we’re going to play the mystery card) as the attributes of conscious persons, persons-in-relation. For example, rocks don’t instantiate those attributes. Cows don’t either. And neither do zygotes. Zygotes in the womb are POTENTIALLY persons with a holy and loving character. But they aren’t that as zygotes. So to say these three attributes are the only really necessary attributes of divinity that can’t be set aside is to say they’re instantiated at all times by Jesus.

So tell me Nelson, where is the Son/Logos immediately post-conception, when, given your kenoticism, the Son was reduced to being a two-celled zygote in Mary’s womb? How is the Son instantiating as this zygote what you agree are the necessary, divine and irreducibly personal attributes of a loving and holy character?

Tom

LikeLike

Nelson,

1) “In the beginning was bthe Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made.”

John 1:1-3

then…

He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him. And he is before all things, and in him all things hold together.

Colossians 1:15-16

then…

Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world. He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power.

Hebrews 1:1-3a

Scripture seems to affirm that the God the Father’s method of originating and “upholding” Creation is His creative Word, who is Christ. I don’t know of any texts that disavow the statements above, effectively saying that God creates and upholds WITHOUT His creative Word.

—————-

2)The way that I see the creeds, Nelson, is that they, in effect, say what MUST be said in order to answer the following questions within a monotheistic framework:

**How is the crucified Jesus not just seen as Messiah, but also as Lord and Savior of humanity? Said another way, how does Jesus save first Jews then Gentiles from the power of sin and death when, Jewishly speaking, only GOD is Israel’s Savior (Isaiah 43)?**

I submit to you, Nelson, that the only reasonable answer for those questions lies in the early church belief that Jesus was in some way divine. And the creedal statements of the Church were all about honing out the theological implications of saying that Jesus was in some way divine.

So why these questions? For one thing, it seems that Paul (as well as Peter and James, whom he met) believed that the crufixion of Jesus was not merely the governmental execution of a God-honoring Jewish adherent, but a divinely-sanctioned offering for sin. Further, Paul seemed to believe that the resurrection was a validation of Jesus’ sacrifice for sin. Paul specifically states “…if Christ has not be raised, your faith is worthless; you are still in your sins.” Taken with the Philippians 2 text, it seems that Paul believed that Jesus’ exaltation ala resurrection was directly connected with his “obedience unto death.” To Paul and others (like the author of Hebrews), Jesus’ resurrection is inseparable from the saving activity of his life and death on the Cross. Now, if the blood of Jesus is NOT the “blood of God” in some meaningful way, then the idea of Jesus being the **sinless** “Passover lamb” who effected the PERMANENT “propitiation in His blood” of all sin by the shedding of his blood ultimately becomes incoherent. How could Jesus, out of all the people who have ever lived, be the only sinless human being? How can the death of a merely human agent–regardless of how devoted to God–effect such universal salvation AND warrant divine exaltation to being made head honcho over ALL creation, including heaven? If one’s christology doesn’t make sense of those claims, it is terribly deficient to that degree.

All this is to say the following: Any conception of the Incarnation that we take HAS to take the two questions above into account as well as a plausible response. Why? Because it deals with nothing less than our salvation. In Tom and my view, the way the kenotic take works out fails to *adequately* affirm and maintain Jesus’ divinity. On the other hand, the Nicene and Chalcedonian creedal statements of the Church do not fail to do so.

LikeLike

Wow, you guys sure know a lot about what Jesus was feeling on the cross. You must have a lot more inside information than I do. All I have are the gospels. 😉

LikeLike

We aim to please!

LikeLike

Fr. Kimel,

I think you would say the following things:

1) Jesus (the Son in his human nature) authentically felt some level of genuine alienation from His God and Father on the Cross when he spoke the “My God, My God…” language.

2) When Jesus made the “My God, My God…” statement on the Cross, his brain did not experience fulness of joy in His relationship with His God and Father.

3) Jesus did not fail to consider himself his God and Father’s Son on the Cross.

4) The alienation experienced in the Son’s humanity (Jesus) on the Cross in no way diminished the Son’s eternally-occurring experience of fulness of joy in intra-triune relationship with the Father and the Spirit in the uncreated realm.

Would you disagree with any of these statements, Fr.?

LikeLike

My answers to:

1) I honestly thought that the omission of “subsistence” was accidental.

2) By accepting the fact that the Incarnation is a paradox, I’m accepting the fact that any imaginative construct of it by me is by nature inadequate, because God is greater than what my mind can grasp. So, I must ensure that I don’t confuse my imaginative construct of the Incarnation for the reality of the Incarnation.

However, I must submit my own imagination to God’s revelation in Jesus, according to Scripture. If my imaginative construct goes against what’s stated in Scripture, or if I give more weight to something other than Scripture, I must at least be suspicious of it. Most of the time, however, we are unaware of the limitations and errors in our own views, even if we’re sincere in our search for truth. That’s why we must engage with other brethren and discuss our believes, and study Scripture together. And that’s why I’m engaging with you: so you’ll point out the inadequacies in my imaginative construct of the Incarnation (be it kenotic or whatever) using Scripture.

3) I have no problem with hypostatic union, per se. I just believe that love is the divine hypostasis (foundation, essence, subsistence) that unites divinity and humanity. I believe the Logos became flesh (not just acquired flesh) to re-establish the union that Adam lost. Basically, I believe the order of events expressed in Philippians 2:5-11: the eternal Logos, not considering His equality with God as something to hold on to, stripped Himself of the form of God and took on the form of a servant, further humbling Himself by remaining faithful until he died on the cross; therefore, because of His faithfulness, the Father exalted Him, recompensing His humanity with the privileges of the divine (Daniel 7:13,14). It’s interesting that Paul’s main topic in this passage is not the Incarnation but the love that motivated it. I still don’t understand how can God become human, but I believe it wholeheartedly because it is in Scripture.

Your lucid dream analogy makes the “two natures, one person” conceivable to the imagination. But the question remains: How? Like I said, I don’t think we can answer that question until the Kingdom is manifested and we see Jesus as He is.

Regarding where the Logos was post-conception, I believe He was in Mary’s womb. I don’t see any other alternatives in Scripture. Maybe you can direct me to literature that directly addresses the problems with kenoticism or write a post about it. I would be very much interested.

4) I did not say that pointing out wrong or even heretical interpretations of Scripture is inherently arrogant. I just said that when it comes to something as ineffable as the Incarnation, transcending human understanding, it would be arrogant of me to think that I have figured it out and that those who disagree with me are heretics. I can express my opinion that those who disagree with me might be wrong, just as I could be wrong. But to declare them heretics entails that I know their hearts, which I don’t. And to declare any given interpretation of Scripture as inherently heretical is not conducive to dialog, as it does not leave room for debate. (Who wants to be labeled a heretic?) If I disagree with any given view about a Christian teaching, I must use Scripture to substantiate my claim.

5) I understand that in your version of the hypostatic union the divine nature transcends the human nature. However, a human being cannot transcend his/her own humanity. If the Logos became flesh, then it must have been in a way that conformed to human nature as created by God. The Logos became flesh; that is, the Logos became immanent. The Incarnation is just the culmination of the process God started in Creation. That is what I believe Scripture teaches.

6) Jesus is the human being par excellence. We human beings are designed, predestined and called to have characters that reflect God’s holiness and love. Because of sin, we are unfaithful, and our characters fail to express God’s holiness and love. God’s holiness (faithfulness to Himself) and love (God is love) are built into the design for humanity. Jesus is the only human being who remained faithful to God’s original design. So you see, Jesus is the human expression of God’s love. And He’s holy because he remained faithful to His calling to express God’s love. Was he holy in the womb? Was he loving in His becoming a one-cell zygote? Did he fail to instantiate God’s love? You tell me. I certainly believe he was holy, loving and the perfect instantiation of God’s image. I believe it with all my heart.

P. S. – If John the Baptist, a man conceived by human parents (though the greatest of prophets, and full of the Holy Spirit since in the womb) was capable of praising God from the womb (Luke 1:41-44); then, why is it difficult to believe that Jesus, conceived of the Father through the power of the Holy Spirit, did instantiate love towards the Father by the power of the Holy Spirit. There is mystery involved in the Incarnation of the Son of God, after all.

LikeLike

Thank you Nelson. There’s a lot there and I’ll try to stick to it.

I agree God is greater than what our minds can grasp. I also agree that our best constructs are inadequate to capture the divine reality. I agree too that all our thinking must submit to Scripture. And I agree that we should engage in and do theology with others. No disagreement on any of this.

As for the inadequacies of kenoticism, our objections are on record. It seems extremely implausible exegetically/Scripturally, unnecessary philosophically, and theologically disastrous. If I’m following you, then I don’t think you embrace anything like the orthodox view on the hypostatic union. The phrase is a technical term for the orthodox position. There aren’t “versions” of it (you speak of my ‘version’ of it; but it’s not “my” version). It just is the Orthodox position on the union of the two natures in the one person of the Son. You can borrow the phrase “hypostatic union” and use it to express other unorthodox views, a kenotic view for example, but it’s not use of words that orthodoxy invites us to. It’s a shared meaning and worldview. And kenoticism denies those.

I can’t follow your comments on heresy; on the one hand you don’t think it’s arrogant to point out heretical interpretations of Scripture. So you agree there are such things and the Church can identify them. I agree. But on the other hand it seems you think that to declare someone a heretic “entails that you know their hearts, which you don’t.” Here it seems you think identifying heresy has to do with knowing peoples’ hearts. Which is it?

I agree it’s arrogant to think we have the incarnation all figured out and that every disagreement is a heresy. But that’s not to say we can’t know SOME things, and that we ought not to identify SOME things as heresy with respect to Christology. Does identifying a view as ‘heretical’ hamper dialogue? Yes. Does anyone WANT to be labeled a heretic? I don’t imagine so. Is your point here that since identifying heresy is hard on dialogue we ought not identify it? Or that since SOME disagreements are allowable, there’s no such thing as heresy? For the record, Dwayne and I aren’t declaring heresy here. But we don’t mind appealing to Church history and Councils on important matters of Christology where heretical views were identified after decades and decades of debate.

Nelson: Was he loving in His becoming a one-cell zygote? Did he fail to instantiate God’s love? You tell me. I certainly believe he was holy, loving and the perfect instantiation of God’s image. I believe it with all my heart.

Tom: The question isn’t, Was the Son loving “in becoming flesh”? We can both agree on that. The question is, Was the Son in unbroken, eternal and uncreated fellowship with the Father and the Spirit WHILE he was also a zygote in the womb? I know this sort of nit-picking seems irrelevant to (virtually all?) Evangelicals, but’s that’s because for us Evangelicals the answer to the question has no perceived consequence for our understanding of salvation or our spirituality and THAT is what Dwayne and I lament.

Nelson: If John the Baptist, a man conceived by human parents (though the greatest of prophets, and full of the Holy Spirit since in the womb) was capable of praising God from the womb (Luke 1:41-44); then, why is it difficult to believe that Jesus, conceived of the Father through the power of the Holy Spirit, did instantiate love towards the Father by the power of the Holy Spirit.

Tom: Are you suggesting that John the Baptist’s prenatal experience makes it possible to suppose that the zygote (of Jesus) in its CREATED natural capacities (reason, consciousness, volition, etc.) is in conscious, loving fellowship with God AS a zygote? Nobody doubts that the preborn (especially in the last trimester) are impressionable and can be affected by the mother’s state of mind and other influences. Certainly. But we’re not even talking about ‘created being’ at this point. The Son/Logos is uncreated, and our question is about THAT, i.e., the UNCREATED relationship to and enjoyment in love of the Father and the Spirit. The zygote can’t simply be THAT in/by means of its created natural capacities. It grows into a responsibly functioning adult (Jesus) who comes to participate in that uncreated life (just like we do), but we think the created zygote cannot AS a zygote be the sum total of the uncreated Son’s existence within the Trinity.

LikeLike

I think it misses the larger issue to say that a co-substantial trinity is paradoxical. The real issue seems to be that it is undefinable in the way we define every thing definable. It’s part of the whole negative theology problem. So much is denied that nothing positive is left to serve as a definition. Hence, no analogy is conceivable. If the Son is conceived of as having attributes, it would seem the Son is a substance. But this is denied in the co-substantiality doctrine. But then what is the attribute being attributed TO? Just throwing out the letter concatenation “hypostasis” is of no avail if it doesn’t correspond to anything humans have a category for. And if it does thus correspond, why not just use modern language to communicate the idea? Have all modern folk managed to fail to come up with a word for a category we all have?

Moreover, I see no analogy between a dream, which is merely mental content, and a bona-fide conscious prehension OF at least some extra-mental aspects of reality, which latter is what the 2-mind view is supposed to “mean.” Indeed, if “Jesus” isn’t a distinct person, but only a name we give to a distinct stream of consciousness running “parallel” to another (what that conscious experience is to be attributed to, words fail to communicate seemingly), what/who ever suffered in any sense whatsoever? If neither “Jesus” nor the “Son” is a real substance that we can attribute (verb) an attribute (noun) to, it seemingly wasn’t either of them that suffered if “suffering” is an accidental attribute of a substance. And if “suffering” isn’t an accidental attribute of a substance, what is it? A substance? A length? A duration? What?

In short, it seems that co-substantiality of undefinables renders any “relation” between those undefinables equally undefinable (i.e., incapable of being prehended conceptually and hence communicable linguistically). In other words, the creeds can’t communicate linguistically what they seem to attempt to communicate. As has been said elsewhere, the mere “words fail.”

Interestingly, I heard Hart claim that he deemed Richard Swinburne as misguided in his theology as ID’ers, supposedly are. Because even though Swinburne supposedly adhered to creeds, he seemingly wouldn’t deny enough of God to suit Hart to properly “interpret” the creeds.

This is why the whole labeling (heretic, idolater) thing is of no avail. It ends up being just another way of the “non-heretic/idolater” saying “I disagree with you on this point but can’t explain what I believe on the matter in conventional language.” But why would anyone care about that if the labeling one can’t explain what he/she believes in conventional language? In which case, why continue with the labels? They’re void of conceptual meaning to the idolater/heretic. Why not just say “I disagree but can’t explain my position to you linguistically.” That’s a lot less disrespectful sounding, and it means the only thing communicable to the putative idolater/heretic in the first place.

It makes sense for those who already agree to use the labels to communicate succinclty TO ONE ANOTHER what they disagree with. But there’s no clear value in using the label in the context of trying to change the mind of the one you disagree WITH. But the labels aren’t limited this way. Coakley throws the idolater label to Robert Lawrence Kuhn with no apparent sense of corresponding obligation to help him linguistically out of his putative idolatry. What is Kuhn to make of this non-constructive labeling by the non-idolaters?

LikeLike

Excellent Post, Tom. I started to read the comments, but only got so far before my head started spinning.

What I find extremely significant is that the “cry of dereliction” is the first verse of Psalm 22. The psalmist goes on the say in verse 24,

For he has not despised or scorned

the suffering of the afflicted one;

he has not hidden his face from him

but has listened to his cry for help.

So while I don’t doubt that Jesus may have felt abandoned, I believe he finished this Psalm, and knew that he was not abandoned, and looked forward to the hope of Glory even on the cross:

As the Psalm concludes, in vv 25-31:

From you comes the theme of my praise in the great assembly;

before those who fear you I will fulfill my vows.

26 The poor will eat and be satisfied;

those who seek the Lord will praise him—

may your hearts live forever!

27 All the ends of the earth

will remember and turn to the Lord,

and all the families of the nations

will bow down before him,

28 for dominion belongs to the Lord

and he rules over the nations.

29 All the rich of the earth will feast and worship;

all who go down to the dust will kneel before him—

those who cannot keep themselves alive.

30 Posterity will serve him;

future generations will be told about the Lord.

31 They will proclaim his righteousness,

declaring to a people yet unborn:

He has done it! (It is finished?)

This echoes the author of Hebrews who said in 12:2, “For the joy set before him he endured the cross, scorning its shame”.

God did not forsake Jesus on the Cross. That was the thought of the pharisees: ” He trusts in God. Let God rescue him now if he wants him, for he said, ‘I am the Son of God.’” (Matt: 27:43), “and yet we considered him punished by God, stricken by him, and afflicted. (Is 53:4).

They considered Jesus forsaken on the cross by the Father, but he was not. The Father was with him all along.

Hebrews 13:5 “”Never will I leave you; never will I forsake you.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tom, I also think your analogy of the dream is really interesting. I’ll have to share with you my thoughts on virtual reality, Zimzum, creation and the mind of God some other time!

LikeLike

Subscribing to this thread

LikeLike

I like this quote: ‘In Christ, humanity trusts in the face of all evidence to despair. There is only unquestioning obedience and trust: “I am my Father’s Son right here, right now, on this Cross, no matter what this nightmare says I am”’. But the general article I don’t know…

LikeLike