Readers here know how fond we are of Greg Boyd. We appreciate his insight and passion, his conviction to make Christ the center and goal of faith, and his heart for marginalized people. And of course we, like Greg, are open theists. We have a lot in common.

Readers here know how fond we are of Greg Boyd. We appreciate his insight and passion, his conviction to make Christ the center and goal of faith, and his heart for marginalized people. And of course we, like Greg, are open theists. We have a lot in common.

Readers might remember that last spring we challenged claims Greg made about the Cross constituting an essential break in the triune relations between the Father, Son and Spirit. Greg’s Christology had become not only not Orthodox or Chalcedonian (which is hardly by itself an immediate concern to Protestants today) but more interestingly in Greg’s case a definite departure from positions and conclusions he argued for in his doctoral work Trinity & Process about which we’ve shared.

Presently Greg is sharing a series of posts (three posts thus far: 1 here, 2 here, and 3 here) that explore his and ReKnew’s theological commitments regarding the Incarnation. Greg’s renewed interest in the Incarnation, his kenoticism, his departure from core commitments made in Trinity & Process, his widespread influence upon readers and — well — the fact that we’re such fans all are reasons why we wanted to engage his recent posts and, hopefully, convince folks to think long and hard about his views on the Incarnation before climbing aboard.

Chalcedonian Christology

In this post Dwayne and I would like to clarify what is involved in the “two minds” view of the Incarnation. A cup of coffee with Fr Rick at St. George’s in St. Paul might have saved Greg the embarrassment of having published so badly misunderstood an account of what the two minds view is. In this post we wanted to set the record straight. Folks ought to know that Greg’s description of the two minds view is inaccurate — too inaccurate to overlook.

In his third post Greg differentiates between the Chalcedonian Creed (451 AD) and ways theologians have understood and applied this Creed. The Council of Chalcedon was the fourth ecumenical council called primarily to address debates over the nature of Christ’s humanity and the relationship between the humanity and divinity of the Son. Their conclusion? The well-known phrase: One person, two natures (divine and human) “unconfusedly, immutably, indivisibly, and inseparably” united in one person “without the distinction of natures being taken away by the union but rather the property of each nature being preserved….”

Here we’d like to point out that Greg simply misunderstands the two minds view. How’s he understand it? He explains:

“This view holds that Jesus walked the earth with both the all-knowing mind of God and the limited knowledge of a human being…[T]his tradition concludes, Jesus somehow simultaneously possessed ‘two minds’: a divine omniscient mind and a human finite mind.”

And also:

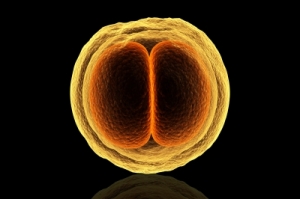

“It requires us to imagine that Jesus was aware of what was happening with every molecule on every planet in the universe even while he was a zygote in the womb of Mary. And it requires that we imagine this while also affirming that, as a fully human zygote, Jesus was completely devoid of any awareness.”

This isn’t the two minds view at all. But for the moment notice that for Greg, Jesus is all there is to the Logos. Incarnation just means the eternal Son, the Father’s personal Logos, is reduced without remainder to the constraints of a human, embodied context. And this embodied space — and only this space — constitutes the sum total of the Divine Logos during his earthly career. The logic is simple: Jesus is God. Jesus isn’t omniscient or universally present. Therefore being omniscient and universally present isn’t necessary to being God. Simple. But there’s more. Since Jesus as a zygote in Mary’s womb is also the sum total of the Divine Logos post-Incarnation, we can also dismiss (along with omniscience and omnipresence) something Greg doesn’t explicitly mention, namely, that personal consciousness is essential to divine being. We know this (following Greg’s logic) because zygotes aren’t remotely conscious or personally related subjects and because the zygote in Mary’s womb is the Incarnate Logos (and thus divine), and because this zygote is all there is to the Logos. Therefore, being divine can’t necessarily involve being or doing anything a zygote is not being or doing. As Greg explains:

This isn’t the two minds view at all. But for the moment notice that for Greg, Jesus is all there is to the Logos. Incarnation just means the eternal Son, the Father’s personal Logos, is reduced without remainder to the constraints of a human, embodied context. And this embodied space — and only this space — constitutes the sum total of the Divine Logos during his earthly career. The logic is simple: Jesus is God. Jesus isn’t omniscient or universally present. Therefore being omniscient and universally present isn’t necessary to being God. Simple. But there’s more. Since Jesus as a zygote in Mary’s womb is also the sum total of the Divine Logos post-Incarnation, we can also dismiss (along with omniscience and omnipresence) something Greg doesn’t explicitly mention, namely, that personal consciousness is essential to divine being. We know this (following Greg’s logic) because zygotes aren’t remotely conscious or personally related subjects and because the zygote in Mary’s womb is the Incarnate Logos (and thus divine), and because this zygote is all there is to the Logos. Therefore, being divine can’t necessarily involve being or doing anything a zygote is not being or doing. As Greg explains:

“I would rather argue that the Son of God set aside the exercise of his omniscience in order to become a human, for, I would argue, being non-omniscient is part of what it means to be human. I would argue the same for any other divine attributes that contradict the meaning of ‘human’.” (emphasis ours)

There you have it. Whatever is essential to being divine must be realizable within and as the limits of finite, created human being. Greg thus holds that the human and divine experiences of the Logos are exhaustively coterminous with the experience of Jesus (from his being a zygote onward). Divine uncreated being is therefore neither necessarily all-knowing, nor all-present, nor need it be a subject of a personally related experience at all (as zygotes are not instances of personal consciousness).

What of the two minds view? Well, Greg explains it in terms of his own view of the Incarnation. If there are two minds (divine and human), they have to be minds coterminous with the state of Jesus’ human consciousness. But the human consciousness of Jesus was clearly not omniscient. Hence, Jesus doesn’t have two minds, one finite and limited and one divine and infinite. (Actually, as a zygote, on Greg’s view, the Incarnate Logos doesn’t even have one mind, but never mind that.)

None of this is Chalcedonian two minds Christology. The two minds view does not hold that the human consciousness of Jesus (or Jesus as a zygote) was both omniscient and not omniscient. The two minds view in fact agrees that Jesus’ finite embodied human nature was neither everywhere present nor omniscient. But it doesn’t follow from this that the personal experience of the Logos was reduced to his human experience as Jesus. Rather, there is more to the Logos than the human experience we call Jesus, and it is this Logos who is the personal subject of both a fully divine and a fully human experience. Thus the two minds view is that the personal experience of the Logos is not coterminous with or reducible to his human experience. True, the Logos is truly present as incarnate human being. But “truly” present here need not mean “merely” present. There is more to the Logos post-Incarnation than Jesus.

Don’t believe us without checking things out for yourself. There are several Orthodox we could call upon, but space limits us to one. Athanasius (in On the Incarnation) will do:

“The Word was not hedged in by his body, nor did his presence in the body prevent his being present elsewhere as well. When he moved his body he did not cease also to direct the universe by his mind and might. No. The marvelous truth is, that being the Word, so far from being himself contained by anything, he actually contained all things himself…

“As with the whole, so also is it with the part. Existing in a human body, to which he himself gives life, he is still source of life to all the universe, present in every part of it, yet outside the whole; and he is revealed both through the works of his body and through his activity in the world. It is, indeed, the function of soul to behold things that are outside the body, but it cannot energize or move them. A man cannot transport things from one place to another, for instance, merely by thinking about them; nor can you or I move the sun and the stars just by sitting at home and looking at them. With the Word of God in his human nature, however, it was otherwise. His body was for him not a limitation, but an instrument, so that he was both in it and in all things, and outside all things, resting in the Father alone. At one and the same time—this is the wonder—as man he was living a human life, and as Word he was sustaining the life of the universe, and as Son he was in constant union with the Father…”

This, friends, is Chalcedonian two minds Christology. It is not the human which possesses two minds. It is the contingent human as finite mind which is possessed by the Logos in addition to his ever-abiding and essential divine experience. God’s eternal Logos thus possesses two minds, one divine (with its divine experience as the infinite, abiding image and creative Word/Logos of the Father sustaining the cosmos including Jesus’ own embodied experience) and one human (with its human experience as the finite Jesus). One person — two natures.

This, friends, is Chalcedonian two minds Christology. It is not the human which possesses two minds. It is the contingent human as finite mind which is possessed by the Logos in addition to his ever-abiding and essential divine experience. God’s eternal Logos thus possesses two minds, one divine (with its divine experience as the infinite, abiding image and creative Word/Logos of the Father sustaining the cosmos including Jesus’ own embodied experience) and one human (with its human experience as the finite Jesus). One person — two natures.

Greg misunderstands the historical position because he equates “mind” with “person” (one mind = one person; two minds = two persons, etc.) and takes Jesus to constitute the sum total of the person of the Logos. But the Orthodox relate “mind” with “nature.” So naturally for the Orthodox the Logos is one person with two natures, one divine and one human, each nature possessing its respective mind and will, irrevocably united in the one person of the Logos without confusion, etc. But confusing the two is precisely what Greg does.

We can’t think of an issue that commits one to take a stand on divine transcendence more than the issue of the Incarnation of God’s Son. Greg’s view, like all kenotic views, has no room for transcendence. For Greg there cannot be more to the Logos than there is to the embodied, finite Jesus. There can be no transcendent experience of a divine nature belonging to the person of the Logos outside the four walls of Jesus’ human experience. This is evident in Greg wondering how Jesus can run the universe from Mary’s womb. We wouldn’t have the slightest idea how that could be. But that’s not the two minds view. Rather, as Athanasius explains, it is the Logos who runs Mary’s womb from the universe, not the other way around.

More to come.

(Picture of Mary and Child.)

[…] – the biggest of which are probably that this is not all the tradition meant to assert (a complaint raised by Boyd’s colleague Tom Belt here), and that they can’t get rid of all the apparent incompatibilities between humanity and […]

LikeLike

Perhaps it might be salutary to recall the words of the Athanasian creed: “Who although he is God and Man; yet he is not two, but one Christ. One; not by conversion of the Godhead into flesh; but by assumption of the Manhood by God.”

Boyd appears to believe that an authentic incarnation is only possible if the eternal Son somehow changes. He needs to cease being who he is in order to be truly human. He needs to relinquish his divine attributes so that he might experience a genuine human existence. It almost sounds like a science fiction story, doesn’t it? One day the eternal Son wakes up not knowing who he is, not knowing anything of his divine existence and identity. He lives his life, discovers that he has a prophetic calling from God, ends up getting crucified, but awakens in eternity on Easter morning with all of his former memories restored. It makes a great story. We could probably make a good movie about it. But it’s also mythology.

Boyd has been tricked by the temporal language of “God became Man.” But consider how things look if we complement the “becoming” language with the language of the Athanasian creed–God assumes human nature.

If I may, I’d like to re-quote a passage from William Temple that I posted in your comments last spring:

By its very nature, Chalcedonian Christology is paradoxical and antinomical.

I want to suggest that Boyd’s problem (and it is a problem shared by many) perhaps originates in his theistic personalism. Once one rejects classical theism, radical kenoticism virtually becomes inevitable. Why not think this way? Perhaps this kind of kenoticism is the logical conclusion of theistic personalism. Hmm–need to think more about this.

LikeLike

Another way of saying what I am so poorly attempting to express is this: if our trinitarian and christological reflection is not grounded in the radical transcendence (i.e., difference) of the Creator, then we are bound to mess things up. This is one reason why proper reflection on the biblical story cannot bypass the theology of the Church Fathers. The creatio ex nihilo may not be explicitly stated in the Bible, yet it is an essential biblical doctrine that is presupposed in the trinitarian and christological reflections of Orthodox Christianity.

Boyd poses a conflict between being divine and being human, as if God and creatures exist on the same ontological plane. Hence when God steps onto the world stage and becomes Man, something has to give–either God displaces the creature or God ceases to be Creator. In effect, Boyd treats Deity as a finite being.

LikeLike

Tom, how do we reconcile Aidan’s claim that we can’t even make intelligible sense of a divine being with attributes and the claim that we can coherently account for a being that has all the essential attributes of BOTH a human and a divine being? The traditional trinitarian view posits that neither the Logos nor the Father is a BEING. At that point, attributes don’t have their normal meaning. You need to be specific enough to show that you’re intelligibly solving a discernible and intelligible problem. Best I can tell, the EO don’t claim we’re even doing that if Aidan is accurately articulating in their behalf.

On the other hand, we know the OT claims the Messiah would be CALLED “God.” In the NT, he was, indeed, called “God.” But we also see in the NT that the Father is called the “one” God. What we see there is the application of an already obviously wide-ranging term, “god,” to different contextual conveyances. Taken this way, there never was a problem, much less an insoluble or unintelligible one.

LikeLike

Let me immediately offer this qualification: I am NOT speaking on behalf of Eastern Orthodoxy. I do not know Eastern theology sufficiently to make such a claim.

LikeLike

Thanks for the clarification, Aidan. But Tom has not explained his position clearly either. He seems to be claiming he can know when a human category is transcended by God even when he’s presented no evidence of that. That would seem to mean that his belief is either humanly self-evident or that it is the product of private revelation. The former seems quite implausible, and the latter seems to render all logical discourse (of the kind he’s trying to articulate on the blog) irrelevant to the plausibility of the belief.

As for ex nihilo creation, it is clearly the most parsimonious explanation of our experience. And it is perfectly intelligible once a causal complex is properly understood to mean the antecedent necessary and sufficient existential conditions of those subsequent existential conditions we call the effect.

LikeLike

“And it is perfectly intelligible once a causal complex is properly understood to mean the antecedent necessary and sufficient existential conditions of those subsequent existential conditions we call the effect.”

What? 🙂

LikeLike

Jeff, I’m not sure what you’re asking. The problem Dwayne and I are trying to engage is a very old one, and that is how is it that Jesus is both fully divine and fully human and we’re decidedly against kenotic approaches like Greg’s. That’s all.

As for making intelligible sense of divine being, I think Fr Aidan’s point is the same point you and I discussed on the ‘David Hart at Biola’ post for quite some time after which we agreed to disagree, and that point regards the nature of divine transcendence. I don’t claim to know “when a human category is transcended by God” (if that means some are and some are not transcended). I believe it’s all transcended all the time. But I’ve been unable to satisfy your requests for proof of such transcendence.

LikeLike

[…] For more, see An Open Orthodoxy: Reknewing Christology Part One. […]

LikeLike

Aidan, how else can you define a cause and make sense of how we use it deductively to explain things? That definition is completely consistent with ex-theo creation, which is what people mean by ex nihilo creation.

LikeLike

On the other hand, if you’re saying we can make sense out of God causing His own existence, well of course we can’t. But we can’t even conceive of the question once we, as you, deny that God is a being. The fact is, neither you nor Tom has explained how perpetual existence PER SE has to be caused. If only changes of existential STATE require causes, ex nihilo creation can only mean what we mean by ex-theo creation. And that’s what scripture SAYS, whatever it was intended to MEAN. But one would think that what it says just MIGHT be what the author meant.

LikeLike

Jeff, I’m having a hard time deciphering your language. If you can, please regard me as philosophically untrained and translate your points into layman’s language. Thanks!

Given that Tom has not yet responded to your comments—I imagine he is out working in the Lord’s frozen vineyard today—let me offer a couple more comments of my own.

1) You write: “He seems to be claiming he can know when a human category is transcended by God even when he’s presented no evidence of that.”

This is an easy one: all of our human categories are transcended by God. This follows from the creatio ex nihilo. The only question really is what kinds of positive or analogical statements may we make about God.

2) You write: “how else can you define a cause and make sense of how we use it deductively to explain things? That definition is completely consistent with ex-theo creation, which is what people mean by ex nihilo creation.”

I don’t understand why you have raised this regarding anything I have written. In any case, I disagree that creatio ex nihilo and creatio ex theo are equivalent, unless that latter is explicitly defined as synonymous with the former. A Neo-Platonist understanding of emmanational creation might reasonably be described as creation from God.

It seems to me that we have moved well beyond Tom’s article. His principal thesis is that Greg Boyd has misunderstood the logic of Chalcedonian christology. The purpose of Chalcedonian christology is not to describe the inner psychology of the God-man, but to prescriptively govern Christian discourse about him. There is simply no need to move into the kind of radical kenoticism that Boyd has advanced—at least there’s no need to do so if one holds a proper understanding of divine transcendence.

LikeLike

Aidan: This is an easy one: all of our human categories are transcended by God. This follows from the creatio ex nihilo. The only question really is what kinds of positive or analogical statements may we make about God.

J: If by creation ex nihilo you mean something other than creation ex-theo, then I agree. But how do you know creation ex nihilo is true in that sense?

Aidan: There is simply no need to move into the kind of radical kenoticism that Boyd has advanced—at least there’s no need to do so if one holds a proper understanding of divine transcendence.

J: If by transcendence you mean a transcendence of our categories, then the question is this: Does transcedence INCLUDE the import of our categories? If so, our categories are all that is relevant to understanding language and how that language guides us in choice adjudication. Because however our categories might be transcended by God, I have no idea what the import of that transcendence is. What is unintelligible is irrelevant to choice adjudication. And Christianity is as LEAST about proper choice adjudication, is it not? Or do you deny that libertarian free-will has any relevance to Christian life?

LikeLike

J: “If by creation ex nihilo you mean something other than creation ex-theo, then I agree. But how do you know creation ex nihilo is true in that sense?”

I believe that God created the universe from out of nothing because it is the dogmatic teaching of the one holy catholic and apostolic Church and apart from which the conciliar teachings on the Trinity and Incarnation do not make sense.

J: “If by transcendence you mean a transcendence of our categories, then the question is this: Does transcedence INCLUDE the import of our categories? If so, our categories are all that is relevant to understanding language and how that language guides us in choice adjudication. Because however our categories might be transcended by God, I have no idea what the import of that transcendence is. What is unintelligible is irrelevant to choice adjudication. And Christianity is as LEAST about proper choice adjudication, is it not? Or do you deny that libertarian free-will has any relevance to Christian life?”

Jeff, rather than attempting to address your questions directly, I think I’d rather put matters more starkly and bluntly: the Almighty God is utterly unknowable and incomprehensible in his essence/substance. We do not know what God is. You ask for clarification about the import of that transcendence. The immediate and most important consequence is the generation of humility and awe. The second consequence is the recognition that our language for God is apophatically-determined. God is infinite mystery. We do not know what we are talking about. In the words of St Thomas Aquinas:

The question of adjudication that you raise is, quite frankly, of secondary importance. What is important is the recognition of the divine ineffability and incomprehensibility. A good place to begin is Aquinas’s Summa, Part 1, question 3.

But now we have wandered far, far from Tom’s article.

LikeLike

Aidan: Jeff, I’m having a hard time deciphering your language. If you can, please regard me as philosophically untrained and translate your points into layman’s language. Thanks!

J: Maybe you can help me too. What’s the “Neo-Platonist understanding of emmanational creation.” As for “necessary and sufficient conditions,” it’s the same idea required for any valid deduction. If the import of premises are sufficient to imply a particular conclusion, the deduction has a valid form. Causal explanation is deductive in form.

LikeLike

Let me first make the disclaimer that I’m not a kenoticist. A kenoticist starts with an idea of who/what god is and is not, usually presupposing a certain incompatibility with and separateness from humanity, and then tries to fit that conception of god unto Jesus. However, I’d rather start with Jesus and learn from Him who God is, because Jesus fully reveals who God is. This is actually something Greg Boyd reiterates in his sermons about Kingdom ethics, but that I think he fails to take into account when it comes to his theology of incarnation. If we start with Jesus, kenosis is an unnecessary concept.

My main disagreement with your post is that your definition of the two-minds Christology differs little from Boyd’s.

Boyd: This view holds that Jesus walked the earth with both the all-knowing mind of God and the limited knowledge of a human being. (http://reknew.org/2014/01/did-jesus-have-two-minds/#sthash.vRndBeag.dpuf)

OpOrtho: This, friends, is Chalcedonian two minds Christology. It is not the human which possesses two minds. It is the contingent human as finite mind which is possessed by the Logos in addition to his ever-abiding and essential divine experience. God’s eternal Logos thus possesses two minds, one divine (with its divine experience as the infinite, abiding image and creative Word/Logos of the Father sustaining the cosmos including Jesus’ own embodied experience) and one human (with its human experience as the finite Jesus). One person — two natures.

The difference between Boyd’s definition and yours is the locus of the minds. Boyd says that the two minds are in Jesus (which could’ve easily been an slip up). You say the two minds are in the Logos. However, regardless of the locus of the two minds, the problem persists: two minds means two experiences of the same event, a proposition that introduces a division in the person of Christ, further complicated by positing two wills. You even say: “there is more to the Logos than the human experience we call Jesus”; effectively, turning Jesus into an avatar of the Logos. This doesn’t surprise me because Athanasius treats Jesus the same way in the quote you posted. Jesus is “an instrument”.

The traditionally called Athanasian Creed says: “yet he is not two, but one Christ. One; not by conversion of the Godhead into flesh; but by assumption of the Manhood by God”. Well, this proposition is doing a disservice to the gospel of John:

The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth. (John 1:14 NIV)

Καὶ ὁ λόγος σὰρξ ἐγένετο καὶ ἐσκήνωσεν ἐν ἡμῖν, καὶ ἐθεασάμεθα τὴν δόξαν αὐτοῦ, δόξαν ὡς μονογενοῦς παρὰ πατρός, πλήρης χάριτος καὶ ἀληθείας. (ΚΑΤΑ ΙΩΑΝΝΗΝ 1:14 NA28)

John speaks of a becoming flesh, not of assuming flesh. Jesus is not an avatar, or an instrument. Jesus the man is the true revelation of God. Jesus the man is the true image of God. Jesus the man is the true wisdom of God.

It is my opinion that all this confusion about persons, and minds and wills, is the consequence of substituting fourth century Greek philosophical categories for first century biblical Jewish ones.

LikeLike

Nelson: The difference between Boyd’s definition and yours is the locus of the minds. Boyd says that the two minds are in Jesus (which could’ve easily been an slip up). You say the two minds are in the Logos.

Tom: Thank you for the comments Nelson. Appreciate them. I think Greg and Orthodoxy disagree in understanding the “two minds” on more than just the location of the minds. Greg also dismisses the Chalcedonian instruction not to “confuse” the two natures. He pretty much collapses the two.

Nelson: However, regardless of the locus of the two minds, the problem persists: two minds means two experiences of the same event…

Tom: That’s my understanding, yes, though, just to clarify, both experiences belong to the same person.

Nelson: …a proposition that introduces a division in the person of Christ, further complicated by positing two wills.

Tom: There is, if I understand Chalcedon, a distinction of natures to be made in the person of Christ, yes.

Nelson: You even say: “there is more to the Logos than the human experience we call Jesus”; effectively, turning Jesus into an avatar of the Logos. This doesn’t surprise me because Athanasius treats Jesus the same way in the quote you posted. Jesus is “an instrument.”

Tom: I plead guilty to agreeing with Athanasius and to a certain instrumental us of the human by the Logos. I don’t think the ‘person’ Jesus is is an instrument used by the person of the Son/Logos because I think the person Jesus is is the person of the Son/Logos. His human nature and embodied context are USED by the Logos. I don’t know if this commits me to viewing Jesus as the “avatar” of God because I don’t know what you mean by avatar.

In Hinduism, an avatar is the descent of a deity to Earth. As I understand it (and I’m not expert on Hinduism) this descent is translated as “incarnation.” I don’t know how compatible Christian and Hindu understandings are at this point. If you’re defining an “avatar” as a deity descending to earth without “turning into” (i.e., without being reduced without remainder to) some earthly form, then yes, that’s just Orthodox Christianity. If that’s the Hindu understanding of incarnation, that’s fine. It would just mean that Hindus are closer to Orthodox Christianity on this one point than Kenotic Evangelicals are.

But if you’ve got the movie Avatar in mind, then no—I certainly don’t view the instrumentality involved in Incarnation in those terms. What happens in that movie would translate into Christianity as the Logos just wearing a man flesh suit. Jake Sully simply shuts down or hibernates his human context and downloads his consciousness without remainder into an avatar flesh suit. That’s not what Orthodoxy has in mind at all. Actually, Nelson, that’s what Greg has in mind. His would be the ‘avatar’ view (if you have the movie in mind).

Nelson: John speaks of a becoming flesh, not of assuming flesh. Jesus is not an avatar, or an instrument.

Tom: I don’t know what you mean by avatar, and there are competing understandings of ‘instrumentality’ here. I make instrumental use of my body. You do of yours. Why wouldn’t God the Son make instrumental use of his body? Are you thinking that if the Logos somehow enjoys a personal experience that includes but exceeds the constraints of his embodiment, this would empty his human experience of its integrity and reality? Why suppose that?

John says the Word ‘became’ flesh, yes. Do you take “became” here to mean something like “turned into” or “was changed/transformed into”? That’s not going to work—especially if you’re not a kenoticist (and you say you’re not), in which case you have to view the “becoming” in some ways an “assumption” or “addition.” Besides, “became” isn’t the only NT word used to describe the incarnation. You also have the Son “taking the form” of a slave, “being found in appearance as a man,” and 1Tm 3.16 (speaking of the mystery of the Incarnation) that says “he appeared [or was revealed] in the flesh.” So yes, the Son “became” human. But it’s the “same Son” through whom the world came into existence who became human, and he never stopped being that PERSON.

Nelson: It is my opinion that all this confusion about persons, and minds and wills, is the consequence of substituting fourth century Greek philosophical categories for first century biblical Jewish ones.

Tom: Well, I’m as eager as anyone to have my confusion dispelled. So by all means, tell us precisely which philosophical categories and terms we should dump and which first century biblical Jewish categories we should limit ourselves to so as to clarify the Incarnation. I’m all ears.

LikeLike

Tom: I don’t think the ‘person’ Jesus is is an instrument used by the person of the Son/Logos because I think the person Jesus is is the person of the Son/Logos.

J: So the Logos is not a person sans creation either? Nor the Father?

LikeLike

Oh, I think I follow you now, Tom. You say “But it’s the ‘same Son’ through whom the world came into existence who became human, and he never stopped being that PERSON.” So are you saying that Jesus is a fourth “person?” I don’t see how it solves the problem of defining what is meant by “same Son” once we say the Son is not a being. What would the Son then be? An attribute of a being? A distance? A duration? Some other relation? A frame of reference for a class of relations like time and space?

LikeLike

Once we accept the obvious fact that the word “god” in Greek and Hebrew doesn’t fit narrowly in any philosophical conception of “god,” we have no reason to assume that multiple persons/beings is problematic either philosophically or theologically. 1 Cor. 8 tells us explicitly that there is ONE God — THE FATHER. The OT says the Messiah would be called God. He is and was. Jesus himself called the Father the ONE, TRUE God. There is a clear indication as to the sense in which the Father is that ONE God. It’s that the Father ALONE is He OUT OF whom are all things. But what the NT reveals to us is that the Son is also a necessary condition of creation as well, but in the sense that it is he THROUGH whom are all things. For all I know, this may imply something as parsimonious as that the Son had to consent to creation since it involved the possibility of his own suffering. No human category denial is required to make sense of it, however much those categories might be transcended! Transcendence is not the same thing as contradiction.

LikeLike

And I’ve yet to understand why we are to posit distinctions that aren’t in scripture and explain nothing about our experience (like “the Father eternally begets the Son,” as if scripture ever speaks of the Son as BEING a son except in the sense of incarnation, creation, and ressurection) while denying distinctions that are expressly IN scripture (like, all things are out of the Father but through the Son).

LikeLike

Tom: I don’t think the ‘person’ Jesus is is an instrument used by the person of the Son/Logos because I think the person Jesus is is the person of the Son/Logos.

Jeff: So the Logos is not a person sans creation either? Nor the Father?

Tom: F, S, and SP are persons in relation eternally. Jesus in this person (the Logos) incarnate. One and the same ‘person’. So my point to Nelson was that ‘the person who Jesus’ is cannot be an instrument of ‘the person of the Logos’ because they are one and the same ‘person’. But the human ‘nature’ (embodiment, finite mind, the natural capacities that define Jesus’ embodied context) IS the instrument of the ‘person’. But this is a little beside the point. Nelson seems to object to this human context being transcended by the person because he supposes (it seems) that if there’s more to the person of the Logos than this limited/finite embodied context of his human experience, then that embodied context is just an “instrument” of the person of the Logos—to which I reply, ‘Yes, so what? This is a good thing.’

Jeff: Oh, I think I follow you now, Tom. You say “But it’s the ‘same Son’ through whom the world came into existence who became human, and he never stopped being that PERSON.” So are you saying that Jesus is a fourth “person?”

Tom: Not at all. There’s no person additional to the person of the Logos.

LikeLike

Tom: There’s no person additional to the person of the Logos.

J: So to be clear, the two-minds view you hold asserts:

1) Jesus is not a person.

2) Humans are persons.

3) Jesus is not fully human.

4) The Logos is fully human.

Is that it? I still don’t see how to square the notion that the same person can accurately believe contradictions. And that seems to be what is entailed in positing that one mind is consciously aware of possessed capacities that the other mind is consciously “aware” of lacking. That would seem to mean that it is not the person that possesses the capacities, but the minds. But if there are no other capacities than mental capacities, then what IS a person such that it’s distinct from a mind? And if we can’t distinguish a person from a mind, then the two-mind view just becomes the two-person view.

LikeLike

Jeff: So to be clear, the two-minds view you hold asserts:

1) Jesus is not a person.

2) Humans are persons.

3) Jesus is not fully human.

4) The Logos is fully human.

Tom: You’re jokin’ right? You’re yankin’ my chain.

1) Jesus is a person, the 2nd person of the Trinity, the Father’s Logos.

2) Yes.

3) No. Jesus is fully human.

4) Yes.

LikeLike

Jeff: So to be clear, the two-minds view you hold asserts:

1) Jesus is not a person.

2) Humans are persons.

3) Jesus is not fully human.

4) The Logos is fully human.

Tom: You’re jokin’ right? You’re yankin’ my chain.

1) Jesus is a person, the 2nd person of the Trinity, the Father’s Logos.

2) Yes.

3) No. Jesus is fully human.

4) Yes.

J: So for clarification:

1) Jesus is fully human [your 3)]

2) Humans are persons [your 2)]

3) The fully human Jesus IS the Logos [your 1)]

4) The logos is a person and fully divine

5) Jesus is a person [your 1)]

So Jesus is a person and the logos is a person. On the one hand, you seem to want there not to be 2 persons there. But then what IS a person? How are you distinguishing person from mind such that 2 minds doesn’t just MEAN 2 persons? Define the terms. See, Tom, in the good old days, the mind was considered a subset of what a person is. Sentient capacity was conceivee of as distinct from mental capacity. But that creates the problem:

“I still don’t see how to square the notion that the same person can accurately believe contradictions. And that seems to be what is entailed in positing that one mind is consciously aware of possessed capacities that the other mind is consciously “aware” of lacking. That would seem to mean that it is not the person that possesses the capacities, but the minds. But if there are no other capacities than mental capacities, then what IS a person such that it’s distinct from a mind? And if we can’t distinguish a person from a mind, then the two-mind view just becomes the two-person view.”

LikeLike

There aren’t any emoticons to express what I…

Jeff, whatever works for you. Whatever helps you love God with all your heart, soul, mind and strength. Let’s just agree to meet there and enjoy that until Christ returns.

Tom

LikeLike

That agreement has always been, Tom. You express disagreement with Greg. And so on. That’s the nature of theology. It’s like any other “ology.” There are different perspectives. And if the LNC is valid, they can’t all be right. You’re saying Greg is wrong. Does that mean you haven’t “agreed to meet Greg there and enjoy your own perspective?” Of course not. What then is the difference?

LikeLike

Heh Tom and Dwayne, happy to see your on-going interest in my Christological reflections. We’ve hashed most of this out before, so I won’t address your particular criticisms. I’ll just make one comment that I believe forges new ground in our dialogue. I think you may be right that I would have better represented the way most defenders of the classical Christology speak by saying the LOGOS, rather than Jesus, simultaneously had an omniscient and non-omniscient mind. Having granted this point, however, I’m not convinced I “embarrassed myself,” as you put it. Surely you’ve come across some of the many defenders of the classical Christology throughout history who interpreted some things Jesus said in the gospels as deriving from the omniscient Logos (e.g. “Before Abraham I Am”) and others from his non-omniscient mind (e.g. Mark 13:31, “no one knows… not even the Son”). So too, they interpreted some of things things Jesus did as deriving from his omnipotent divinity (e.g. the miracles) while others derived from his humanity (he grew in tired, and usually, his suffering). How is this NOT admitting Jesus simultaneously had an omniscient and non-omniscient mind (and was omnipotent and non-omnipotent)?

Not only this, but is it not true that in the classical Christology, the Logos IS Jesus and Jesus IS the Logos? If so, how can you avoid saying JESUS simultaneously has an omniscient and non-omniscient mind? To deny this seems to entail either a) that the Logos is not fully Jesus, and vice versa, and/or b) that Jesus as Logos and Jesus as human is divided (a la Nestorianism).? So, in sum, could you please explain how you two DENY Jesus simultaneously had an omniscient and non-omniscient mind while avoiding both of these heretical implications? . Thanks. GB

LikeLike

Tom: John says the Word ‘became’ flesh, yes. Do you take “became” here to mean something like “turned into” or “was changed/transformed into”? That’s not going to work…

Nelson: Why not? Why reject the plainer meaning of the word for a more forced one?

Tom: You also have the Son “taking the form” of a slave, “being found in appearance as a man”…

Nelson: You’re quoting Philippians 2:5-11. You correctly point that Christ takes the form of a slave. However, you have to take into account the whole context. Paul takes Christ as the perfect example of humility, who being in the form (μορφή, the recognizable display of internal essence) of God, did not consider His equality with God as something to greedily grasp or hold on to (ούχ άρπαγμόν ήγήσατο, see Joseph B. Lightfoot’s commentary on Philippians); but he humble or divested himself, taking the form of a slave. His divine substance (ύποστασις, Hebrews 1:3) remains, while His form is exchanged. Compare this to 2 Corinthians 8:9, where Jesus exchanges His wealth for our poverty. You can’t say His both rich and poor. You can say He has a right to wealth by the nature of who He is, but He chooses not to assert that right.

Tom: So yes, the Son “became” human. But it’s the “same Son” through whom the world came into existence who became human, and he never stopped being that PERSON.

Nelson: Neither Boyd, nor I, are asserting that the Logos became someone else when incarnate. We all agree that the Son remained the Son even after taking the form of a slave.

Tom: Well, I’m as eager as anyone to have my confusion dispelled. So by all means…

Nelson: I’m sorry, Tom. I didn’t mean to suggest or insinuate that I was somehow more enlighten than you or anybody else. I was just trying to express my frustration with the confusion of concepts in fourth century AD theology. One example of this would be the concept of Logos. The concept of Logos of many fourth century theologians seems to conform better to the Stoic logos spermatikos than to St. John’s Logos. The Stoic logos spermatikos is an all-permeating divine force or energy that gives and sustains the universe and its content. Meanwhile, St. John’s Logos is a merge of two Jewish concepts: Wisdom (see Proverbs 8:22-36) and God’s creative utterance (Genesis 1-2:3). (Interestingly, these concepts express action and relation, as oppose to static, abstract essence).

Tom: Nelson seems to object to this human context being transcended by the person [the Logos]…

Nelson: I do not object to the transcendence of the human by the divine in Jesus. I object to the two-mind explanation for this transcendence as incoherent and unnecessary. God made humans in His image, according to His likeness and gave us His Spirit, so there’s already a divine transcendence imbedded in humanity. We lost that divine transcendence because of Adam’s transgression. Jesus is the new Adam, who by His faithful, loving obedience transcends the consequences of the first Adam’s transgression. And this transcendence is granted by grace to whosoever trusts/believes in Jesus the Messiah through the gift of the Holy Spirit.

LikeLike

Nelson, sorry to be so slow in responding. Posts appear over top over posts and I get lost!

Real quickly…

1) I don’t see it as “forced” to read “became” in JN 1 (the Word became flesh) as consistent with the Word’s remaining ‘what’ he was before he ‘became’ a human being. There is no “plain” meaning here as the one you mean.

2) You view the “form of God” Phil 2 as the object of kenosis. So the Word “exchanges” one form (the form of God) for another form (that of a human being), it being impossible for one subject to be the subject of both. But the resurrected/glorified Christ remains the Incarnate One. So it must be your view that the Son’s “divine form” (forfeited in ‘exchange’ for a “human form”) is permanently and irrevocably forfeited, since the Word remains forevermore incarnate in human form. The “form of God,” or the Word’s divine form, is permanently exchanged and thus forever relinquished. Is that right?

3) You say “Neither Boyd, nor I, are asserting that the Logos became someone else when incarnate. We all agree that the Son remained the Son even after taking the form of a slave.” Could you tell me, Nelson, what is it that makes the Son the Son?

LikeLike

Greg, Nelson, et.al.,

To say, with Jesus, that Jesus has a divine mind is simply a way of saying that Jesus has a divine nature. It tells us absolutely nothing about Jesus’ inner psychology or self-awareness or anything like that. The only access we have to the historical Jesus’ inner beliefs are the gospels, with all of their limitations. I think it is perfectly legitimate to speculate about our Lord’s self-awareness, but ultimately I think I agree with E. L. Mascall when he wrote, “It is indeed both ridiculous and irreverent to ask what it ‘feels like’ to be God incarnate.”

Some think that to attribute a divine mind to Jesus we are asserting that the historical Jesus also knew quantum mechanics as well as the Chalcedonian definition itself. But again, this is both to misunderstand the function of the Chalcedonian dogma, which is to grammatically govern churchly discourse about Christ, and to treat divinity as something that competes with Christ’s human nature, so that we end up with a monstrous God-man hybrid.

The kind of kenoticism that you are advocating, which was popular in some 19th century Protestant circles, was finally abandoned because folks realized it was both unnecessary and mythological: unnecessary, because Chalcedon authorizes the Church can say everything about the humanity of Jesus that needs to be said; mythological because the idea of God temporarily jettisoning his attributes in order to “become” human treats divinity and humanity in the same logical world, which they aren’t. That’s one of the reasons the Church Fathers repeatedly insisted that we cannot comprehend the divine nature. We have know idea what “divine” means. Anyone who thinks they do know what “divine” means needs a good dose of the Eastern Fathers or St Thomas Aquinas.

The Chalcedonian definition asserts an incomprehensible mystery, the mystery that is Jesus Christ—that is the dogmatic point, no more, no less.

LikeLike

1. Jesus Christ reveals God.

2. God is a God of order. If we renounce logic, we renounce order.

3. If it’s okay to speculate about how many minds are in Christ, it is good to confront our speculation with the Sacred Text.

4. Everything should be done in love. If in anything I have written I offended anybody, please, forgive me.

LikeLike

“1. Jesus Christ reveals God.”

I agree with this, but of course, one might say that the entire creation reveals God, too. One doesn’t even need to be a Christian in order to affirm this statement.

“2. God is a God of order. If we renounce logic, we renounce order.”

There’s logic and there’s logic. A rational man recognizes those points when his rational powers have reached their limits. If God is indeed the transcendent Creator who has brought the world into being from out of nothing, then he is not an object of scientific and empirical inquiry, and even philosophical inquiry will be exceptionally limited.

To subject the trinitarian and christological dogmas to human logic, as if we know what we are talking about, as if God is an entity within the cosmos, is, I suggest, utterly irrational. The theologians who formulated the trinitarian and christological dogmas did not think they were “explaining” anything. They knew that the Christian mysteries lie beyond comprehension and speech. Their responsibility was to set the doctrinal boundaries beyond which lies distortion of divine revelation.

“3. If it’s okay to speculate about how many minds are in Christ, it is good to confront our speculation with the Sacred Text.”

Sure. But you will not read the Sacred Text rightly if you do not read it through the hermeneutical lens of the trinitarian and christological dogmas. At this point I of course reveal my Orthodox colors. I am not a sola scriptura Christian. Not only is sola scriptura not taught in Scripture, but it doesn’t make sense at all. But that is a discussion for another thread.

The trinitarian and christological dogmas are NOT speculation per se. They stipulate the grammatical rules of churchly discourse and set the boundaries beyond which speculation may not go.

Why confess that the incarnate Son has two minds, divine and human? Because the denial of the proposition effectively denies the divinity of Christ. Why is the kenoticism of Greg wrong? Because at first glance it seems to make sense! It eliminates all the mystery that the Church Fathers were so keen to preserve through paradox and antinomy. But it’s also the case that once one begins to analyze kenoticism more deeply, one recognizes that it does not faithfully represent the apostolic faith.

“4. Everything should be done in love. If in anything I have written I offended anybody, please, forgive me.”

Yes, ditto. Speaking only for myself, Nelson, I have not been offended by anything you have written. No apology is necessary.

LikeLike

Fr. Aidan: …the entire creation reveals God…

Nelson: Amen to that. However, allow me to add nuance to my previous statement. Jesus Christ reveals God uniquely. Creation reveals that there is a god. All other ways of revelation can only offer glimpses of God’s glory. Jesus reveals God perfectly in His humanity (For in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form, [Colossians 2:9 NIV]) and he does it now through the Spirit (these are the things God has revealed to us by his Spirit. The Spirit searches all things, even the deep things of God. For who knows a person’s thoughts except their own spirit within them? In the same way no one knows the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God. [1 Corinthians 2:10, 11 NIV]).

Fr. Aidan: To subject the trinitarian and christological dogmas to human logic, as if……is, I suggest, utterly irrational.

Nelson: The finite mind cannot grasp the infinite God. However, dogmas are human expressions and should be coherent and cohesive. Otherwise, all of theology is out of place.(I prefer poetical expressions over theological statements, but they overlap sometimes). We’re not trying to analyze God’s essence. We’re doing a critical assessment of a theo-logical statement. This is both rational and necessary.

Fr. Aidan: …you will not read the Sacred Text rightly if you do not read it through the hermeneutical lens of the trinitarian and christological dogmas

Nelson: The Trinitarian and Christological dogmas are not suppose to be lenses through which to interpret the Bible. That would be an imposition on the Sacred Text; endogesis as oppose to exegesis. Rather, this teachings are discernible in the Bible. And the Bible is written in rational, logical and human languages. Of course, not everything is spelled out in the Bible. The text cannot contain the Spirit, but the spirits must be tested by the Text. The Holy Spirit’s guidance and the Sacred Scriptures should set the boundaries for Christian theology.

Fr. Aidan: The trinitarian and christological dogmas are NOT speculation per se…

Nelson: What I am questioning is the two-mind doctrine. I believe this is what beloved brother Boyd is also doing. We both believe in the Trinity, we both believe in the divinity of the Logos and we both believe that His divinity remained when he became incarnate. We both believe that this is what the Bible teaches. But to say that Christ has two minds is not the same as saying he has a two natures.

LikeLike

Correction: The first sentence should read: “To say that Jesus has a divine mind …”

LikeLike

Waking up this morning and re-reading my comment, I see that I left a couple of typos and did not express myself clearly at a couple of points. Here is the corrected comment. Tom, I’d appreciate if you would substitute it for the original. Thanks.

+++++

Greg, Nelson, et.al.,

To say that Jesus has a divine mind is simply a way of saying that Jesus is united to the divine nature, i.e., he is God. It tells us absolutely nothing about Jesus’ inner psychology, self-awareness, or anything like that. The only access we have to the historical Jesus’ inner beliefs are the gospels, with all of their limitations. I think it is perfectly legitimate to speculate about our Lord’s self-awareness, along the lines suggested, say, by N. T. Wright; but ultimately I agree with E. L. Mascall when he wrote, “It is indeed both ridiculous and irreverent to ask what it ‘feels like’ to be God incarnate.”

Some fear that the attribution of two minds to Jesus implies that the historical Jesus also knew quantum mechanics, as well as the Chalcedonian definition itself. But again, this is both to misunderstand the function of the Chalcedonian dogma, which is to grammatically govern churchly discourse about Christ, and to treat divinity as something that competes with Christ’s human nature, resulting a monstrous God-man hybrid.

The kind of kenoticism that you are advocating, which was popular in some 19th century Protestant circles, was finally abandoned because folks realized it was both unnecessary and mythological: unnecessary, because Chalcedon authorizes the Church to say everything about the humanity of Jesus that needs to be said, historically and theologically; mythological, because the idea of God temporarily jettisoning his attributes in order to “become” human locates divinity and humanity in the same logical world, which they aren’t. That’s one of the reasons the Church Fathers repeatedly insisted that we cannot comprehend the divine nature. We have know idea what “divine” means. Anyone who thinks they do know what “divine” means needs a good dose of the Eastern Fathers or St Thomas Aquinas.

The Chalcedonian definition asserts an incomprehensible mystery, the mystery that is Jesus Christ—that is the dogmatic point, no more, no less.

LikeLike

Aidan: We have know idea what “divine” means.

J: Yes, the inability to define “person,” etc in terms of co-substantial trinitarianism renders your comment true, if indeed you were saying something intelligible BY saying you hold to co-substantial trinitarianism. But you’re admitting, by implication, that the very claim of your adherence is an unintelligible claim.

Where nothing is conceivably given, nothing is conceivably required. All conceivable normativity is out the window once “divine” has no intelligible meaning. In that sense, it creates the same problem atheism does. It renders our very moral nature seemingly the effect of a-benevolent and a-malevolent causality (or a-causality?), just as many atheists would admit.

On the other hand, teleology grounds the intelligibility of common-sensical normativity. But to say God is a teleological designer of the rationally-ordered (and therefore rationally-inferrable) cosmos is to say something INTELLIGIBLE about Him.

Scripture doesn’t even SEEM to be saying Jesus is identically divine as the Father. The scriptural words (greek and hebrew) for god are not meaningless (they’re words, after all), whether or not they help the Chalcedonian position. They allow for the distinction between the “most high God” and less “high” gods, after all.

LikeLike

Our thanks to all for the interaction. I’d like to jump in myself. Just a bit busy.

LikeLike

[…] In one of our latest posts, we featured Tom Belt’s and Dwayne Polk’s series on Reknewing Christology. A bit of an update now: Greg Boyd responded in the comments thread: […]

LikeLike

[…] at Open Orthodoxy Tom Belt has launched a series of articles criticizing the kenotic christology of Greg Boyd. I am not well acquainted with Boyd’s […]

LikeLike

May I suggest that everyone read Divine Humanity by David Brown.

LikeLike

So good to have you visit and comment Sam. For others reading, Sam is a long-term friend of mine and fellow missionary colleague in the Middle East. True lover of God and a passionate thinker! Great to hear from you.

I don’t have a copy of Brown’s book. I’ve glanced at sections of it and have read a couple of reviews. Thorough, very well-written and articulate. Looks like Brown is “the” go-to defender of Kenoticism today. I don’t recall any novel arguments, but it looks like if there is only one book proponents of Chalcedon have to adequately respond to, it would be Brown’s. Thanks for bringing it up, Sam!

One interesting argument for kenoticism that Brown offers is the freedom that kenosis gives to exploring the historical nature of the Christian faith (i.e., the classical two-natures reading of the Scripture is at odds with a modern appreciation of the truly historical nature of gospel textual claims regarding Jesus). It’s unreasonable to expect the apostles and earliest believers to have viewed Jesus in Chalcedonian/two natures terms or to suppose that Jesus’ own self-consciousness obtained in such terms [neither of which is required by the traditional view by the way]. Brown argues that with a kenotic view we “have a secure framework within which Christ’s divinity can be acknowledge without this requiring acceptance of the historicity of some of the more disputed parts of the Gospels.” Basically, the traditional two-natures view requires us to adopt a very conservative reading of the Bible which would not allow the kind of historical…nuances…which a more modern/liberal approach permits. I don’t find this persuasive. There are plenty of Orthodox scholars who are decidedly modern (even errantist) in their view of the texts but who affirm Chalcedon.

And Brown complains (rightly I think) that through most of the history of the classical view it was believed that the two natures of Christ acted and spoke alternately, and studying Christ meant sifting through all his words and actions and attributing this or that one to one or the other nature. He argues that the kind of divided consciousness suggested by this is not at all what the biblical material suggests. Rather, all we have in the gospels is a “single unified consciousness.”

And he writes: “So long as Jesus was thought fully conscious of his divinity, it could plausibly be claimed that trinitarian relations on earth exactly mirror those in heaven. But the more the two-natures model is forced to retreat from such awareness, the more puzzling the claim becomes. At least with modern kenoticism there is presumed to be no other consciousness present on earth apart from the human. So it is Jesus’ humanity in relation to the Father that is seen to reflect heavenly trinitarian relations.” But these concerns pose zero threat to the traditional view that I can see.

Apart from these evidential concerns, Brown argues that Christ’s total identification with humanity is threatened by the classical view. How might WE identify with Christ from within the classical model? What help or support do we find in the Son’s identification with us if it’s true that the Son also enjoys transcendent security and eternal bliss throughout his earthly career? And from the divine side, is the incarnation truly an act of “love” if there is nothing given up? If the triune persons continue to enjoy one another in transcendent unity, how is the incarnation really an act of loving abasement? So Brown views the two-natures treatment of Jesus’ humanity is insufficiently realistic. Greg’s point as well. If there’s more to the Logos than there is to the embodied experience of Jesus within the limitations of his human consciousness (as the two minds view argues) then God doesn’t really identify with us and can’t really be a source of help and encouragement. I think this is easily shown to be false. Maybe I can get back to this later.

I think all Brown’s complaints are easily addressed, while the final chapter (his more constructive part of the book) is woefully weak in its understanding of what divine being essentially amounts to. I’m surprised Greg hasn’t dipped into Brown a lot, because they’re arguments are very similar.

But I think Sam makes a great recommendation. If you can adequately handle Brown’s arguments for Kenoticism, the debate is all but over.

Tom

LikeLike

Tom: If you can adequately handle Brown’s arguments for Kenoticism, the debate is all but over.

J: Not at all. The argument for kenoticism is that the scripture SAYS Christ emptied himself taking the form of a bond-servant and learning obedience by suffering, etc; even the suffering of the cross. It doesn’t say the Logos took on an additional mind. How could it since it would not be meaningful to say that since no one (I’m open to correction!) has either intelligibly defined a deity as a non-being distinguishable from non-divine non-beings and non-divine beings or a person as a non-being distinguishable from a mind?

Without definitions to make the relevant distinctions, we don’t even have a conceivable alternative to kenoticism yet. The only objection to the plain reading kenotic view is the non-scriptural assumption that the phrase “fully divine” has intelligible meaning such that not only is a putatively co-substantial “entity” (being?) called the Trinity “fully divine,” but such that so also is each of its constituent members (F/S/Sp).

I’m pretty sure this is why Adrian admits the hopelessness of the task of conceiving of such a definition. But without a definition of “fully divine,” one can’t even get off the ground to make the argument against kenoticism. Anyone can claim transcendence as a solution to conceptual limitations. Unfortunately, that approach proves too much. It proves that C.S. Lewis was within his rights to say God has exhaustive foreknowledge of the future since He putatively transcends the present in a way we can’t conceive of. No one can win that one since everyone wins by it, rendering the LNC irrelevant, rendering our ability to distinguish non-existent.

LikeLike

J: The argument for kenoticism is that the scripture SAYS Christ emptied himself taking the form of a bond-servant and learning obedience by suffering, etc; even the suffering of the cross.

T: You’re aware it’s possible to read Phil 2 as a non-kenoticist, right?

J: The only objection to the plain reading kenotic view…

T: The word “ekenosen” is certainly there in plain sight. That it plainly means what kenoticists mean is anything but plain. My sense is that Gordon Fee is right. This isn’t a reference to incarnation at all (though obviously it assumes that inasmuch as Paul believes in the incarnation, but it’s not his point here). It’s a reference to Jesus’ humble acceptance of the cross. He ‘emptied himself’ simply means he spent himself for us. But even if Paul has the incarnation primarily in mind, I think a non-kenotic reading is preferable.

J: I’m pretty sure this is why Adrian admits the hopelessness of the task of conceiving of such a definition. But without a definition of “fully divine,” one can’t even get off the ground to make the argument against kenoticism.

T: Please. That’s ridiculous, Jeff. In that case, without a definition of “fully divine” not even kenoticism gets off the ground, for kenoticists insist Jesus is fully divine too. They just all disagreement over what it is that makes Jesus divine.

We have no idea what “fully divine” means. How the he** could we know that? That’s one of the most outrageous things I’ve ever heard you say—and you’re a smart guy. I can know that God, being divine, is “fully divine.” But that’s trivially true. And I can have an idea of something that goes into being divine, something ‘essential’ to it (like necessary personal-relational existence [which itself requires some explanation]). But let’s not require of ourselves or others a definition of “fully divine.”

J: Anyone can claim transcendence as a solution to conceptual limitations. Unfortunately, that approach proves too much. It proves that C.S. Lewis was within his rights to say God has exhaustive foreknowledge of the future since He putatively transcends the present in a way we can’t conceive of. No one can win that one since everyone wins by it, rendering the LNC irrelevant, rendering our ability to distinguish non-existent.

T: I’m sorry Jeff, but you don’t know what you’re talking about (so far as transcendence is concerned). To advocate divine transcendence is not to make every proponent of every view and its contradiction a ‘winner’, or to say that anything can be said of God. But I’m not riding around this cul-de-sac with you again.

LikeLike

T: But even if Paul has the incarnation primarily in mind, I think a non-kenotic reading is preferable.

J: What’s your reason for thinking it’s preferable?

T: It’s a reference to Jesus’ humble acceptance of the cross.

J: And that’s consistent with kenoticism.

T: Please. That’s ridiculous, Jeff. In that case, without a definition of “fully divine” not even kenoticism gets off the ground, for kenoticists insist Jesus is fully divine too. They just all disagreement over what it is that makes Jesus divine.

J: But that’s the point, Tom. A kenoticist is free to suppose that Jesus is fully divine in a different SENSE of the word “divine” in which the Father is fully divine. That’s why the kenoticist need not run into the definitional problems that Chalcedonians do, as Aidan says.

T: But let’s not require of ourselves or others a definition of “fully divine.”

J: I’m not following you. Is it the word “fully” you’re saying we need not concern ourselves with? If so, then I totally agree, and for the reasons I’ve articulated before. The meaning of the greek and hebrew words for god allowed for the contextual use of gods that weren’t even necessary beings or necessary attributes, etc.

T: To advocate divine transcendence is not to make every proponent of every view and its contradiction a ‘winner’

J: No, it’s not if all we mean by transcendence is that God is more than can be conceived with our categories, but is yet not contradictory to them. There are no intelligible winners OR losers if the LNC (which is just the law of identity applied to propositional meaning) isn’t applicable to propositions qua propositions.

How does that play out in particulars? It means that changes in God’s mental states (including new awareness of new LFW choices) are caused, but that we can’t account for the specific cause by our modes of inference. So it’s hard for us to classify God’s truth-belief as what we mean by “knowledge,” since our normal definition of “knowledge” has the notion of explicably non-serendipitous true belief. We can’t explain God’s truth-belief in a way that renders it non-serendipitous, though. We can intelligibly posit certain truth-awareness to God, though.

Now, apply this analysis to your positing that God’s sentient experience is both integrated and void of consciously distinguishable degrees of suffering. Can’t be done intelligibly.

What this means is that what we posit God believes can be used as an explanatory premise. Because beliefs are necessary conditions of teleological ACTION. But what you are saying about God’s sentient experience, because unintelligible thus far, explains nothing about God’s experience or His future action.

So, yes, we need definitions to even communicate. Their lack of exhaustiveness is not the issue. Their intelligibility is.

LikeLike

J: What’s your reason for thinking it’s preferable?

T: On the exegetical side you have Fee’s Philippians commentary. But you can find summaries of him online (http://thetheologicalmosaic.blogspot.com/2011/01/gordon-fee.html. And you’ve also got Rodney Decker (http://ntresources.com/blog/documents/kenosis.pdf). There are others of course.

On the philosophical side there are a couple hundred pages of reasoning in this direction in Greg’s Trinity & Process which I believe you own.

LikeLike

To be clear, it is intelligible to say that God’s sentient experience is integrated and void of suffering IF integrated only means that God consciously distinguishes different degrees of pleasurable experiences only. But even then, that’s not saying that there is a single experience that drowns out all others such that there’s nothing else consciously integrated.

LikeLike

One more suggestion – Studies in the New Testament by Frederic Godet.

LikeLike

Godet! Brilliant at times. But he was one of the best-known kenoticists of his day. He was Gessian (Wolfgang Gess|1819-91) in his kenoticism (i.e., the eternal generation of the Son was suspended and the Logos’ participation in trinitarian relations likewise interrupted for the duration of the Incarnation). Gess explicitly rejected Chalcedon as docetic. As for the generation of the Son being suspended and the triune relations being interrupted, Greg would totally agree (against his earlier work).

LikeLike

Tom: “ekenosen”…..isn’t a reference to incarnation at all… It’s a reference to Jesus’ humble acceptance of the cross. He ‘emptied himself’ simply means he spent himself for us.

Nelson: This interpretation ignores the order of the propositions in the Philippians hymn: form of God, equality of God not held or clutched, divestment or emptying (ἐκένωσεν), then form of a slave and human likeness. This passage (Philippians 2:5-11) is better understood as a pre-incarnation, incarnation and exaltation hymn. The greatest example of love and humility is Jesus Christ (the Logos), who instead of asserting His own divine right, He became a man in the condition of servitude (post-fall humanity) and submitted Himself to obedience (not just to God, but to the kingdoms of this world) but always remaining faithful to His divine calling and nature, even when he knew this meant death – death on a cross! For this, God exalted Him, giving Him the glory He had before the creation of the universe (a Kierkegaardian repetition; refer to John 17:5). (About the Philippians Hymn, see the commentary to Philippians by Joseph B. Lightfoot, available free online at https://archive.org/stream/cu31924029294398#page/n141/mode/1up)

Tom: But even if Paul has the incarnation primarily in mind, I think a non-kenotic reading is preferable.

Nelson: The question should not be: What’s preferable? The question is: What does the Sacred Text say? Which interpretation fits the Text better? Our interpretation should fit the Sacred Text; not the other way around. But if what you meant by ‘preferable’ is ‘fitting’, you case should be made firstly in exegetical grounds.

Tom: …without a definition of “fully divine” not even kenoticism gets off the ground.

Nelson: I agree. However, the beginning of any logical debate is the definition of terms, so the debaters may understand what they’re debating. I know it is impossible for us to exhaustively define what God is. But we can start with a heuristic definition and then work from there. And the one definition of what/who God is was given by Jesus in His ministry. On this we both agree.

Tom: To advocate divine transcendence is not to make every proponent of every view and its contradiction a ‘winner’, or to say that anything can be said of God.

Nelson: But if ‘transcendence’ can be used to support the two-minds doctrine, it can certainly be used to support exhaustive divine foreknowledge of future events. And once ‘transcendence’ has been invoked, how can the debate continue; that is, when the invoked ‘transcendence’ involves the transcendence of logic. How do you handle the argument of ‘transcendence’ when defending open theism? (Note: I favor an open view of God myself).

LikeLike

Nelson,

Thanks so much.

(1) We’re not likely to solve the exegetical issues of Phil 2 here. I hope you don’t think non-kenotic views have no basis whatsoever in exegesis. Gordon Fee (and others) don’t hoist their interpretations onto the text. So yes, by “preferable” I mean “exegetically preferable.”

(2) It doesn’t follow that if divine transcendence helps us affirm Chalcedon that we have no grounds upon which to object to other theological claims (like EDF). There is a proper cataphatic discourse governed by our categories and logic which defines the proper objects of transcendence. So, EDF, Calvinistic determinism, Arianism, Docetism, and a host of other theological errors are not properly said of God. They’re affirmation cannot be apophatically qualified. That is, EDF can’t be transcendently denied because it can’t be cataphatically affirmed.

Apophatic discourse is a strategy adopted to assert that none of the properly cataphatic discourse we are bound to engage in (with all its rightly divided assertions and denials) is a univocal and final owning of the divine reality. It’s as much an aesthetic as it is a rigid set of rules for qualifying cataphatic discourse, which may be why so many struggle with it. Divine reality is not convertible to lines of 1’s and 0’s.

LikeLike

Nelson, the issue, IMO, is this. Tom is exactly right (if I understand him correctly) to say:

“There is a proper cataphatic discourse governed by our categories and logic which defines the proper objects of transcendence. So, EDF, Calvinistic determinism, … and a host of other theological errors are not properly said of God. They’re affirmation cannot be apophatically qualified. That is, EDF can’t be transcendently denied because it can’t be cataphatically affirmed.”

But he’s wrong, I think, to suggest that “divine transcendence helps us affirm Chalcedon.” Why? Because what Chalcedon attempted is to scripture, categories, and logic just what EDF is in the sense that the terms used to express it are not intelligibly definable. This is the very case with EDF. We can’t even intelligibly define LFW if EDF is assumed to be true. But we also can’t rid our minds of the belief in LFW, on the other hand. But we can make perfectly intelligible sense of a non-Chalcedonian conception of those essential and accidental attributes of the godhead that are necessary to explaining our experience, the existence of warranted belief, and a scriptural-hermeneutical method consistent with the criteria for warranted belief.

This doesn’t mean that scripture apart from the Spirit is sufficient. But it does mean that the Spirit only proceeds to reveal beyond the text UPON the believer’s embracing of the best inductive interpretation of the texts.

LikeLike

SORRY FOR THE LENGTH. Take your time.

J: This doesn’t mean that scripture apart from the Spirit is sufficient. But it does mean that the Spirit only proceeds to reveal beyond the text UPON the believer’s embracing of the best inductive interpretation of the texts.

T: I like the sound of that. Don’t know how complete a description it is, but I think it captures something that’s gotta happen. We do have to do, solid, exegesis of texts that takes all the linguistic-historical context into account. I think what it might lack is the role ‘community’ and ‘tradition’ play, and I’m not sure I know what those roles are. But I think our faith proceeds, among other things, upon the “foundation of the apostles and prophets” with regard to Christ. So there’s no laying again another foundation. And we take that on authority. We don’t believe it because we exegete it independently from some text.

And tradition’s authority is implicit in our very faith. We inherently recognize this every time we read our NTs and accept on faith for example that those 27 books (no more, no less) are authoritative Scripture for our lives. We live our very lives within the reach of THESE 27 books, and they didn’t get fixed till much later by a non-Apostolic bunch (the same guys we’re so eager to throw over the side of the boat theologically speaking). Hmmm. But we implicitly attribute an authority to the non-Apostolic Church, convened in council, as cantankerous and imperfect a crowd as they were. If you’re not going to do your own work to independently establish the canon for yourself (with yourself and the tools of discursive reasoning), then you’ve implicitly acknowledged their authority to do so, unless you’re just too lazy, in which case you don’t have much room to criticize. I’m just saying, it’s a bit strange to submit one’s faith on so fundamental a level as defining what one’s Scripture is to be (!) to Church councils whose determination of that very Scripture was informed and guided by their theology, and then deny that theology. That’s very interesting.

J: But he’s wrong, I think, to suggest that “divine transcendence helps us affirm Chalcedon.” Why? Because what Chalcedon attempted is to scripture, categories, and logic just what EDF is in the sense that the terms used to express it are not intelligibly definable.

T: That would be a great argument to make. Seriously. However, I don’t think I’ve said “divine transcendence helps us affirm Chalcedon.” If I did say that, let me correct myself (a bit), because I think Chalcedon proceeds well enough on its own. I don’t want to come across as saying, “Well, God transcends created being in its finitude, so I’ll sweep all the worst and weakest aspects of Chalcedon underneath that carpet in the name of transcendence.” So I don’t think I’m guilty of misusing transcendence the way you describe.

J: This is the very case with EDF. We can’t even intelligibly define LFW if EDF is assumed to be true. But we also can’t rid our minds of the belief in LFW, on the other hand. But we can make perfectly intelligible sense of a non-Chalcedonian conception of those essential and accidental attributes of the godhead that are necessary to explaining our experience, the existence of warranted belief, and a scriptural-hermeneutical method consistent with the criteria for warranted belief.