I’d like to add another point relevant to our understanding of Scripture (from here and here). This point bears less directly on the nature of the Bible’s composition and truthfulness and more on its interpretation and authority. I’m very much in process on this point and hope readers will appreciate the tentative nature of my comments. I’m test-driving this in an attempt to aim in the direction of where I think more settled conclusions are likely to be found.

I’d like to add another point relevant to our understanding of Scripture (from here and here). This point bears less directly on the nature of the Bible’s composition and truthfulness and more on its interpretation and authority. I’m very much in process on this point and hope readers will appreciate the tentative nature of my comments. I’m test-driving this in an attempt to aim in the direction of where I think more settled conclusions are likely to be found.

(6) SENSUS COMMUNIS, or a “communal reading” of Scripture — at least on the essentials. To be sure, there’s certainly a sense one could give to the notion of sola scriptura which is compatible with what we’ve already said in points 1-5. The Scriptures relay that sufficiently truthful historical-social-religious context necessary for the Incarnate One’s self-understanding and vocation. That (i.e., incarnation), we argued, was the primary point of creation and the election of Israel. Naturally, it is to the Scriptures (and not to the Vedas, the Bhagavad Gita, the Avesta of Zoroastrianism or the Quran however profitable they may be) that Christians look to understand those events which ground their self-understanding, their religious inspiration and worship, their ethical core, and their missional/vocational calling. So there’s certainly a ‘sola’ to affirm in this sense with regard to Scripture as the authoritative source of Christian identity and vocation. If that’s all one means by sola scriptura, I don’t know any Christian who would disagree.

But this is not the popular understanding given to sola scriptura by the Evangelicals I grew up with. What’s typically meant is not only that the Scriptures are the authoritative source of doctrine and theology for the Church (there’s agreement there) but that the individual believer is the final arbiter in determining doctrine and belief for him/herself, a kind of creedal sola fidelis (the ‘believer alone’, i.e., ‘my’ reading of the text is the authoritative one for me).

As such sola scriptura entails a certain mistrust of community and with that, of course, of tradition. No surprise on the minimal regard for tradition among Evangelicals. But it may surprise our Evangelical friends who value their identity as ‘relational theologians’ to hear someone suggest that they are in effect isolationist when it comes to finally deciding what the Bible authoritatively teaches; so let me try to describe where I’m coming from.

‘Community’ is promoted as an essential value at the heart of life and belief by relational theologians (like open theists). God and creation are about ‘community’ — communal identity, communally defined and driven mission, crossing traditional boundaries in cooperative efforts to forge a wider and deeper sense of community (because that makes us more like the trinity of divine persons who have their being and identity in community), etc. You get the point—‘being is communion’.

But so far as I can tell this doesn’t translate into how we (Evangelicals of the ‘relational’ sort) finally interpret Scripture, more specifically how the authority of Scripture to determine belief and doctrine is negotiated by the individual. For when it comes to this authority, it seems the individual considers him/herself to be the final arbiter in saying just what that authoritative teaching is. Scripture’s authority effectively reduces to the individual’s authority (to interpret and decide for him/herself). On this point little of the concern for ‘the relational’ survives into how those of us who otherwise value relational being end up determining our faith and identity as Christians. What happens in Evangelicalism is the individual takes sola scriptura to mean Scripture’s authoritative meaning is ultimately fixed for the individual by the individual alone — sola fidelis (the believer alone). After all, individual believers are indwelt and empowered by the Spirit. Shouldn’t this mean final arbitration on matters of interpretation and doctrine, indeed, in saying just what “Christianity” essentially is, rests with each individual believer? Shouldn’t the Spirit’s indwelling and enlightening the individual believer mean the individual is where the Scripture’s authoritative meaning is determined? Only “I” can say what the Christian faith finally is, what its essential beliefs are, etc. True, I’d be wise to listen to other voices, ancient and modern, but in the end, only “I” can finally say what “the faith” is, what “the Church” is, etc. Here the authority of Scripture to settle faith and practice is taken not to describe the boundaries within which the Church is to ‘say together’ what the Church is and believes; rather, that authority is reduced to the individual standing before God. I’m just wondering if this is really the best way to go.

Without wanting to suggest that individuals not read and interpret Scripture but just let other church authorities read it for them and tell them what it means and what they’re to believe (an equal but opposite abuse), I do want to suggest that something is amiss with the sola fidelis reading. The Church after all is Christ’s “body,” a “community,” a “communion” of faith and identity formation. Only that community as a community can decide who they are, what they believe, and what they exist for. To argue that every individual believer is authorized by God to define the Church for him/herself and its faith, as indispensable as the individual is, looks like a failure to maintain a ‘relational ontology’. An irreducibly relational ontology would, arguably, mean a relational or communal reading and understanding of Scripture (sensus communis).

Without wanting to suggest that individuals not read and interpret Scripture but just let other church authorities read it for them and tell them what it means and what they’re to believe (an equal but opposite abuse), I do want to suggest that something is amiss with the sola fidelis reading. The Church after all is Christ’s “body,” a “community,” a “communion” of faith and identity formation. Only that community as a community can decide who they are, what they believe, and what they exist for. To argue that every individual believer is authorized by God to define the Church for him/herself and its faith, as indispensable as the individual is, looks like a failure to maintain a ‘relational ontology’. An irreducibly relational ontology would, arguably, mean a relational or communal reading and understanding of Scripture (sensus communis).

I am, for better or worse, a Protestant. Whatever value sola scriptura might have for Christian unity, Protestants have failed more than any other tradition to achieve or demonstrate it. Now that every individual believer is deputized by the Spirit to determine the meaning of Scripture and identify what the Church and her essential faith commitments are, every believer just is his/her own Church, own faith, own mission. I don’t have a safe, trouble-free path from the ‘text’ (which we all agree speaks with authority) to individual believers, but it seems to me that the Church as a community ought to share in the mediation of this authority if we’re going to be ‘relational theologians’ through and through. This is why I suggest sensus communis, a relational-communal reading of Scripture.

One way to approach this which might help suspicious Evangelicals warm to the idea is to consider that fact that Evangelicals are already implicitly committed to the communal mediation of Scripture’s authority and to a certain extent its key doctrines as well, in their acceptance of the traditional canon. The very texts Evangelicals hold to be authoritative Scripture and whose key doctrines they reserve the right to determine for themselves (as individuals) were in fact settled on by councils on the basis of, among other things, their teaching. These writings and not others were adopted as canon in conciliar agreement on the basis of a shared reading of their content and teachings.

But we cut off the branch we’re sitting on if we agree that these books are our authoritative canon fixed by conciliar agreement but then reject that same authority when it comes to definitive questions of faith and interpretation. It was the authority of conciliar agreement that settled on which texts in fact embody Scriptural authority. So if we accept the standard canon without conducting our own investigation of all the relevant literature to establish the canon for ourselves as independently as we want to interpret it, we are implicitly accepting the authority of the Church’s conciliar agreement to determine for us which books shall speak to us with final authority. But it makes little sense to accept as authoritative the conciliar-communal agreement which fixed those texts we take to be authoritative Scripture if we then dismiss the authority of that same community on matters of interpretation. How do I dismiss the authority of a Church on the basis of authoritative texts whose identity as Scripture I accept on authority of that same Church? Unless I’m going to fix the canon as independently as I want to interpret it, I’m implicitly presupposing the authority of the councils/agreements that gave me the Scripture. The authority of Scripture, then, is mediated communally to me already. I just thought this is a point lost on most Evangelicals and worth considering.

Just thinking on it.

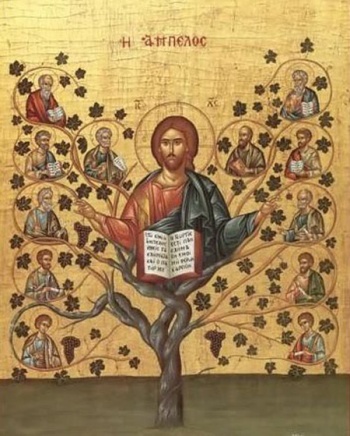

(Picture here.)

As a “protestant” I somewhat disagree. It is not for most of us a conciliar pronouncement on the canon but the witness of the Holy Spirit that confirmed the authority of the gathered texts that now constitute our New Testament. God inspired those texts, not a council. As Peter said: “Judge for yourselves whether we ought to obey God or men.”

LikeLike

I agree. I’d only add that the witness of the Spirit doesn’t operate independently of the community who is recognizing that witness, perceiving the superiority of certain texts over other texts, weighing the abiding attachments that various churches have to particular texts, etc. So that witness has to be made manifest, and it’s made manifest through the communal discernment.

LikeLike

Tom: True, I’d be wise to listen to other voices, ancient and modern; but in the end, only “I” can finally say what “the faith” is, what “the Church” is, etc.

J: I don’t think that’s what most “evangelicals” mean by sola scripture. I think they mean something very much like what logic books say when they (i.e., logic books) say appeals to authority per se are not evidential any sense. The law of non-contradiction, if held by us as valid, tells us that N contradictory statements can’t all be true. That gets us pretty much nowhere.

Induction gives criteria by which many evaluate explanations normatively. Beyond that, it’s very hard to nail down communally (i.e., in terms of what we can reasonably expect everyone to agree on) what we mean by “evidence” or “evincing” apart from one’s own sense of personal credulity or, in religious contexts, private revelation. Even David Hart speaks of the Spirit using scripture like a “lyre” such that TRUE theology is imparted by reading that which can’t impart it. How is that not a species of private revelation?

Paul says anything not of “faith” is sin. And he seems to define the sense of that by saying let everyone be fully-persuaded in his/her own mind. Does that mean an individual is saying “only I can finally say WHAT ‘the faith’ is?” Not as far as I can tell. It seems to mean that the individual is responsible to God for his/her beliefs, not someone else. So that the individual must act on what God has thus far given him/her as intellectually honestly as possible. Will they change their mind along the way about their theology? I know no one who hasn’t.

In short, an inference to who is an authority is seemingly no less an individual inference than an inference to what a text means. Both inferences are seemingly made by the INDIVIDUAL, if they’re inferences at all (as opposed to private revelation or intuition). There’s too many communities and self-proclaimed authorities for any one of them to be what we could reasonably expect everyone to agree on if deduction and induction are the two inferential modes involved. And I suspect the reason why logicians don’t deal with much else is because they themselves don’t know how to nail down other meanings of “evidence” and “evincing” in a way that humans qua humans could ever agree on with any significant probability.

The alternative, seemingly, is to say that there is an evidently true authority and that those who reject it after being “confronted” by the realization of it are just rebellious to it–OR, that they rebelled in the past but have now forgotten that they rebelled thus. All I can say is what Paul said in 1 Cor. 4 with respect to consciousness of wrong-doing. Namely, I have no consciousness of rebelling against what people call “trinitarianism,” because I truly have no idea what it means when I try to conceive of it, let alone whether it could be evincing to me if it were conceivable to me. If I actually understood it once before, and rejected it, and now have forgotten that and therefore can’t know that I once understood it.

This means that if I’m to render “God” as knowable in some sense to humans qua humans, I’m limited in ways that “trinitarians” claim not to be, even if it’s my own fault and can’t remember. Maybe I’ve wrongly chosen my way into a hole from whence there is no return. 🙂

As for the canon, I think induction is the way out of that putative problem. Per induction, you use inductive criteria to determine:

1) whether what seems to possibly be a text even is a text, as opposed to a serendipitous arrangement

2) the meaning of the text

3) whether the meaning of the text is intentional testimony, fiction, or deceit

4) whether the text, if testimony, is plausibly true

By that approach, one need not know a priori which texts are “inspired” in any sense of that word. One just applies induction to see if there are texts that explain or more plausibly explain the rapid rise of a religious sect called “Christians” in the Roman empire in the face of resistance/persecution (after, i.e., inductively inferring that very “rise” of that “sect”). When this is done, lots of folks end up rejecting most or all of what have been traditionally considered EXTRA-canonical texts on those grounds alone, just like C.S. Lewis did. That few convert to Christianity this way has no clear inductive/deductive relevance to the fact of that matter.

LikeLike

In other words, it seems to me that Christianity, if it means anything like what seems to me most people think it means, means that our original community (in the sense that epistemology requires) is the human family. If what is putatively knowable about “God” is such that the only community that has any relevance to the mode of the impartation of the knowledge is some subset of professing Christendom, it would seem that Christian “truth” is non-derivable from language qua language. And that seems to mean that the only way that subset of humanity that constitutes the relevant “truth-holders” (with respect to “God,” at least) could communicate about “God” is if words always serve as “lyres” in the sense of the private revelation David Hart talks about.

In short, it seems to me that one aspect of the criteria used in our discursive voluntary reasoning is almost always a social satisfaction, not merely satisfaction per se (yes, I know one can doubt we reason voluntarily, but I’m assuming open theism is true and intelligible here). The question is, what communion with what community or communities condition those social satisfactions. Which of our beliefs can be taken seriously by which communities and why? For many, including myself, such questions are logically related to what is or isn’t knowable or warrantedly-believed about God. There is no way, IMO, for open theists to have the same view of God if you answer these questions differently.

LikeLike

Thanks Jeff. Let’s hope you’re right about what ‘most’ think. That would be preferable. As I said, I’m just describing my experience with Evangelicals, and my sense is that they tend to view sola scriptura and what I’m calling sola fidelis as two sides of a single coin. If they separate sola scriptura from the latter as you say, good. They still hold to the latter, and that was my primary concern.

As for your concern for LNC, nothing about what I’m suggesting (i.e., sensus communis) per se is self-contradictory or assumes LNC would have to be dismissed as an interpretative method. One could argue that sensus communis (on essentials) should never violate the strict constraints of LNC (LEM, etc.). That’s fine.

Jeff: Even David Hart speaks of the Spirit using scripture like a “lyre” such that TRUE theology is imparted by reading that which can’t impart it. How is that not a species of private revelation?

Tom: Not familiar with Hart on that. But what Hart would never suggest that a private interpretation can ever be thought by any individual to be “the faith” (which is precisely what we have innumerable instances of among Protestants) simply because that’s what God told him the faith is (and he never violated LNC). Species of private revelation is what Protestants are famous for, not the Orthodox.

Jeff: It seems to mean that the individual is responsible to God for his/her beliefs, not someone else.

Tom: I’m not suggesting otherwise. Specifically, I’m not suggesting that sensus communis means individuals are not responsible for what they believe. While the ‘individual’ is responsible to God for his/her beliefs, ‘communities’ are responsible for their beliefs too.

Jeff: Namely, I have no consciousness of rebelling against what people call “trinitarianism,” because I truly have no idea what it means when I try to conceive of it, let alone whether it could be evincing to me if it were conceivable to me.

Tom: I didn’t know you had finally rejected trinitarianism. I don’t see the Church laying the Creeds aside and redefining the faith to include Arians. That’s tough.

LikeLike

Only have time to adress your last response at this time, Tom.

Tom: I didn’t know you had finally rejected trinitarianism.

J: I don’t know what it means to even get to rejecting it.

Tom: I don’t see the Church laying the Creeds aside and redefining the faith to include Arians.

J: I don’t know how you determine what the Church is, for one. I take it to be those persons who believe in their heart that Jesus is Lord of creation and that God raised him from the dead.

Second, I’m not sure what you mean by Arianism, but Wikipedia says it includes:

“The Arian concept of Christ is that the Son of God did not always exist, but was created by—and is therefore distinct from—God the Father.”

I don’t believe the Son was created at any time. I believe the Son is a necessary being. But “trinitarianism” is essentially the denial that the Father and the Son are beings and therefore necessary beings. I don’t know what that leaves us. Because I sure can’t make sense of the Father, e.g., being an attribute of a being, a location, a duration, a temporal or spatial frame of reference or any other category or combination of human categories. And I don’t know how humans qua humans can form concepts with intelligible import apart from combinations of those categories.

And, yes, I know you use the terms “being” etc to speak of the Father, etc, but you then insist that that very language fails to communicate what is actually true of God, leaving those very words unintelligible to me. But you seem to be confusing things. Because it’s almost as if you’re saying that if the Father is a “being” then He could be put in a petri dish. Of course that doesn’t follow at all. If the Father is a “being,” then, by my conception of “being,” He must also have attributes. Can we know that we know all those attributes? No. Just like I don’t know all your attributes even if you’re a being. But that doesn’t mean I can put you in a petri dish. Nor does it imply it.

LikeLike

Thanks Jeff. Sorry to assume Arianism on account of your rejection of trinitarianism. It’s the more common route.

LikeLike

I think first and foremost is the need to consider the context in which the NT was written. If I were back there reading, say, Romans just a bit after Paul wrote it, what would I be thinking? How would I interpret it according to the times in which I was living, as both an individual Christian and budding communal Christian? Would I have suspected Paul or Peter or John to have inferred that I could not have interpreted what I read without the aid of the community of believers? If this were so, who would I have turned to for help? the leader of the local house-church where I worshiped? the town bishop? (Oddly enough, there is little to nothing about establishing church governance in the NT. There are only base requirements for leadership and instructions to a few about conduct in the church.) Further, would I have deduced that Paul’s letter to the Romans was somehow divine or inspired more so than another Christian’s writing. If the bishop back then had said this was so, should I have believed him?

Almost two millenia later, here I am reading such a collection of letters and documents purported to be the truth about the matter of my faith, and the process getting the collection to where it is today was not only not an easy task but is quite controversial. But the question still is am I be allowed to interpret Scripture myself or do I need to consult with my local pastor, bishop or president of my denomination? The answer is…yes!

It is, as Tom noted in response to the first poster, that it was, and is (unavoidably) the community of believers (and sometimes non-believers!) that form the crux of doctrine to be accepted as established truth. For a Protestant it IS the various denominations that make for a rich community of believers in establishing matters of doctrine and worship. Denominations speak of the community of believers as those who are in agreement (or at least used to be) in most but not all matters of doctrine, and have found a means to address the differences.

Go back to the founding of any major (and most of the minor) denominations and you will find very close harmony among them with regard to the essential and cardinal doctrines that have driven the church since the Reformation. The fringe elements simply allowed for somewhat major but secondary doctrines to be established as well, and for the expression of worship flavored to fit a particular style. This made it possible for, say, Calvinists and Arminians to find expression of worship suitable for their like-minded kind.

I am a firm believer that not only is there nothing wrong with the concept of denominations for establishing doctrinal truth (outside the essential core beliefs of the Christian doctrine) but that this accords more to the nature of participation of the human element in communal worship. We see differences in life and cultural all over the world, and, indeed, we welcome such. How is it, then, we cannot see differences in the interpretation of Scripture and worship and not welcome such as well (again, within the limits of essential Christian doctrine)?

With all due respect to the singular form of the Orthodox church system of worship, there is confinement that is, in my opinion, restrictive towards allowing for the development of the interpretation of Scripture and the expression of such in worship. This is not to say that the Orthodox system does not “work,” but compared to Protestantism the Orthodox system works because it confines expression of its laymen. Merely claiming that the Orthodox system is the oldest form of worship, reaching back to the early church, is not to grant it the only form of worship. If Protestantism were the fruit of the lives lived in the Spirit, it too would work much better than it has. That the Orthodox church has a built-in protection from much of the chaos that has ensued within Protestantism is a plus, but that still does not grant it the the truest or only form of worship.

It is and always will be the community of believers, be it a small or great community, that will find itself forming an authority for both interpreting Scripture expressing worship, and expecting, for orderly sake, adherence to final product. This is life. This is how we live.

LikeLike

I was always taught that solo scriptura meant that Scripture alone is the only foundation for faith and the Christian community. However, I could not agree more that Evangelicalism has an extremely personalistic bent when interpreting Scripture. in fact, I would call this incipient Pietism almost fundamental to Evangelicalism. Therefore, if personal experience and application become the primary use of Scripture then you are correct in saying that the final authority must be the individual reader.

That scripture is first and foremost communal, is seen in its very formation. The gospels and almost all of the letters were written to Christian faith communities. When Paul says we are the temple of the Holy Spirit he is speaking first about the church as the communal body. He then goes on to apply it two individual believers.

I spent 4 years in Bible College and did not learn till many years later that the first sermon of Jesus in Luke chapter 4 is about social justice and not about personal salvation. I’m sure that most evangelicals in the pews have no idea of the difference because most preachers don’t recognize the difference…even though that is the plain and literal meaning of the words.

LikeLike