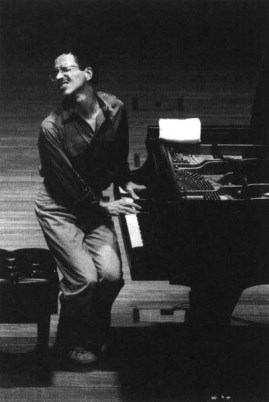

American pianist Keith Jarrett. It might not be your thing, but I promise, if you set time aside to sit, quietly and alone, and listen to his 1997 CD “Las Scala” (named after its venue, the Teatro alla Scala in Milan), you shall be transfigured. Well, not literally. But “La Scala” is a musical Mt. Tabor, an unveiling within finite human capacity of God’s creative design. Now, as you listen, keep in mind that Parts 1 and 2 are live improvisations. He’s on stage—creating. Yeah. The final rendition of “Over the Rainbow” is an equally beautiful improvisation upon that wonderful piece.

Improvisation. What’s it have to do with God and us? Everything, I think.

I seem to find myself in conversations about created freedom and divine will these days. And part of what often creeps up in these conversations is a certain fear of occasionalism that attends the claim that God knows creation only by knowing himself (i.e., his own sustaining acts within creation). It can’t be, so I’m told, the case that God knows I’m typing these words “because” I’m typing these words. That would suggest God is being “acted upon” by my typing, and that can’t be. God’s knowledge of the world cannot be the effect in God of our doing that which he knows we’re doing. So God doesn’t “get” his knowledge of the world “from” the world. This does seem to reduce creation to the divine will as a mere ‘occasion’ for the latter. The answer I seem to get from my Orthodox friends on this is, not surprisingly, “It’s a mystery.” I’ll leave that as it is. I think there’s plenty of mystery in a certain sense of “mutuality” too, but I don’t want to get into a dispute over that here. Rather, I wanted to share a question I asked David Bentley Hart (regarding God’s will for human being as such) last Spring. Let me share the question and then come back at the end to make a suggestion regarding this whole debate over God’s will and created freedom.

My question to Hart:

On p. 320 of Beauty of the Infinite, with reference to Michel de Certeau’s “Autorités Chrétiennes et Structures Sociales,” you concede the possibility that in our final fulfilled form Christ offers (in Certeau’s words) “a style of existence that ‘allows’ for a certain kind of creativity and that opens a new series of experiences” as opposed to, say, Christ specifying every particular of our continuing existence without remainder (even if, as you say, Christ comprises the fullness of every contingent expression).

My question has to do with created agency as fulfilled in Christ and enjoying a ‘scope of loving possibilities’ within which to freely/creatively determine how it shall reflect divine beauties. Going with Certeau’s suggestion, might we imagine the logoi of created beings as embodying or specifying a “range” or “scope” of beautiful expression and not the particular of every form? The divine will (or logoi) would terminate not in the final form of creaturely expression but in the range of creative possibilities offered to creatures to uniquely shape their expressive form (unique not in the creation of beauties not already comprised in Christ as the summum bonum, but simply as the creature’s contribution to the consummate beauty of ends synergistically achieved). Would the gnomic will retain a unique function in this case?

Hart’s reply:

Sure, works for me. I know that Maximus often speaks of the gnomic will as simply the sinful and deviating will. Something tells me–more a phenomenology of consciousness than a moral metaphysics–that it might be better to think of it as the “third moment” of the conscious act, so to speak, the first two being the primordial intention of the natural will and the power of intellect (both being rational). Then the gnomic will is that supremely rational moment of (ideally) assent or love or creative liberty that completes the “trinitarian” movement of the mind and makes it genuinely rationally free. That is obscure. Sorry. But, yes, I prefer to think that, healed, [the gnomic will] remains, and that it makes each soul’s reflection of and participation in divine beauty a unique inflection or modulation of the whole, which makes each individual indispensable, of course, to that glory. (emphasis mine)

The conversation was generally about the gnomic will. But the relevant point is the terminus of the divine will being the provision of a ‘scope’ or ‘range’ of beautiful expression, not the specific form that expression finally takes in created particulars. I hope you see how consequential this is for the question of God’s will in its immediate sustaining of creation as such, on the one hand, and the determination of creation’s actual expressive forms, on the other hand. These are not convertible ‘ends’. That is, God’s will in sustaining is assymetrical (we don’t share in sustaining our existence, we are given being), but what God gives is itself a “scope” of possibilities whose particular determined forms are not asymmetrically willed by God; they are left to created agency to decide. (I see some squirming going on as some read this.)

I’d like to suggest that this should shape how we understand God’s relationship to creation as qualifiedly mutual—that is, asymmetrical (non-mutual) in the giftedness of life because the logoi are God asymmetrically present in us, but truly mutual in the gift’s improvisational return to God. A Bach composition or a Gershwin piece offers a scope or range of interpretive expression. These are never played twice the same way, nor can they be performed at all apart from some interpretive license. This is not due to any limitation in those who play either composer. It is what Bach and Gershwin wanted. It was their will to be thus improvised upon. And apart from that, improvisational license is inherent in any creative act.

I’d like to suggest that this should shape how we understand God’s relationship to creation as qualifiedly mutual—that is, asymmetrical (non-mutual) in the giftedness of life because the logoi are God asymmetrically present in us, but truly mutual in the gift’s improvisational return to God. A Bach composition or a Gershwin piece offers a scope or range of interpretive expression. These are never played twice the same way, nor can they be performed at all apart from some interpretive license. This is not due to any limitation in those who play either composer. It is what Bach and Gershwin wanted. It was their will to be thus improvised upon. And apart from that, improvisational license is inherent in any creative act.

If the logoi of created beings can be analogously understood, then the divine will ends in defining the ‘scope’ without prescribing or determining the actual creative expressive ‘form’ which Truth, Beauty, and Goodness take in us—as us. But this means, I believe, that God’s will in sustaining creation as such embraces created improvisation on our part, which means—I’m afraid to utter it—the divine will (viz., logoi) is given to us to improvise upon. I mean, if you want to retain mystery, there you are. The endless possibilities are God’s, their final arrangement is ours. But if this is his will, then it seems to me that the mode of God’s knowing creation would reflect the mode of his willing; that is, God would know the improvisational form which divine logoi finally take in us as a knowledge of form ‘apprehended’ or ‘received’ and not only a knowledge of created being as ‘given’. What the world gives to God is what it gives back to God in improvisation upon and within the grace of being.

Prayer

You are the themes, the scope, the rhyme

We improvise upon in time,

Are not made less giving away

Your temporal form to what we say;

These forms are what you will to be,

A mirror of your Trinity.

So, if I read this right, Tom, God provides the “conditions of possibility” that determine the range of potential creativity, but the person creatively manifests freedom in how the music is played. All of this is necessarily speculative. For a Sartrean existentialist, there is no essential nature, so freedom is radically untethered. Of course, it is also radically in despair, coming from nowhere and destined for nothingness. The gnomic will is protected from that kind of aimless freedom by a logoi gifted by a loving Creator. The question as your ponderings indicate is what is the nature of the determination given in the original gift? Is a person’s favorite color a manifestation of a singular logoi? Is this part of what is given and must necessarily be realized? Is that sort of thing left open for subsequent choice? Is God surprised when Tom likes purple?

Here is where I am at. Freedom understood as a choice between good and evil, the gnomic will as it is understand in our current dispensation, is obviously something destined to disappear in the fullness of the eschaton. But this even now is a defective understanding of freedom. If “metaphysical freedom” is the flourishing of a nature as it is intended by God — and if nature’s plenitude requires grace, requires rising above the limits of nature to the richness of the person — then it is better to say that freedom is a creative expression of love. This means that all truth is inherently “dramatic.” The goodness of the other surprises in beauty, the truth is manifest through a faithful and dynamic “living with” the other in which ever new possibilities of disclosure are discovered. Here, the freedom of choice is a way of discovering the good simply. What this means is that the depths of the given arise in each unique encounter. What is discovered is new for everyone, for the one giving as much as the one gifted — just as in friendship, we discern elements and capacities in ourselves that we did not know about prior to our unique encounters. This sort of thing should be understood as radically open-ended in eternal life.

Hence, there is something like time, what Balthasar calls “Supertime,” in Triune Life. Those who reject this as an attack on God’s perfected plenitude and an implicit smuggling in of becoming are conceptually confused, in my opinion. I tend to think they are too bound by “Euclidian” thinking and have missed the essential paradox of Christian revelation. My view is that Pure Act is not opposed to Drama. How is it that time should have wonder and surprise and joyous event and somehow God should be static accomplishment without “improvisation”? One may object, this is true for God’s relation to God, but not God’s relation to the creature. My answer is that the gift of theosis, the raising of the cosmos as God’s beloved, a created partner, includes genuine depths. If they are utterly comprehended so that freedom is merely a manifestation of “the expected,” one is closer to a very delicate machine than to the dance of life. But really, one has to be careful who one says all this to.

Fortunately, in most places, burning at the stake is now unlikely.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Beautifully stated. Thank you Brian. I’m just finishing up Nichols’ intro to Balthasar. Enjoying it a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Balthasar definitely has some insights useful to your ongoing inquiry, Tom.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brian, I’m sorting through a few online pieces on Balthasar’s notion of super-time and, as far as I can tell, I like it. Maybe I’ve done a very poor job of expressing myself via the phrase “specious present” which I’ve been using, but as far as I can tell, what Balthasar is saying is what I’m trying to express as well.

I don’t know him at all, but Eunsoo Kim did a PhD on God and time through comparing/contrasting Barth and Balthasar’s views. He writes:

Given this little to go on, it seems to describe what I’m trying to get at with the phrase “specious present.”

Gimme 10 years read some Balthasar.

Tom

LikeLiked by 2 people

Tom,

You might find something useful in Antonio Lopez’s article, Eternal Happening, God as an Event of Love. I tried to link to it, but apparently I just can’t get the hang of simple things like that. Lopez wrote a pretty good book called Gift and the Unity of Being. He needs more lyricism and for my taste, a poetic awareness of strangeness that accompanies wonder. I think you’ll know what I mean because your aesthetic taste seems to bear this. Anyway, the article is good, though occasionally dry and difficult.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You mean this I think:

Click to access lopez32-2.pdf

Thanks! I’m on it.

Tom

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks again Brian. Enjoyed it a lot. Definitely has me processing a few possibilities. I might post some ideas in the next day or so.

LikeLiked by 1 person