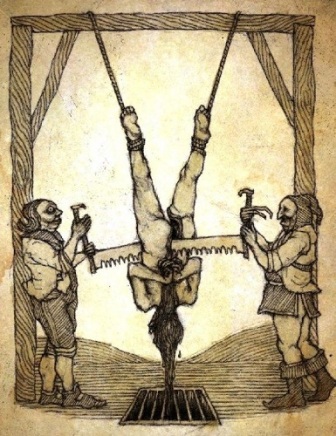

Why the gruesome picture? Because sometimes theology gets in the way.

Why the gruesome picture? Because sometimes theology gets in the way.

I continue to contemplate the crucifixion. Where was God? What was he up to? What was his part in this? What happened there that day which God gives to faith to perceive that so radically transforms the world? God-talk these days is full of references to ‘divine withdrawal’, and to the Cross as the quintessential manifestation of divine withdrawal. I’d like to reflect here a bit upon that idea.

• If we understand God to be inseparably present to creation (as its creator and sustainer – a fairly unobjectionable reading of Scripture), then talk of God “withdrawing” from can only be a figurative expression for the phenomenological aspects of our suffering. We experience ourselves and the world in ways we explain by removing God from the scene. If God were “here,” here would be different that it is, so God must “really” be somewhere else; he must have withdrawn himself.

• But it cannot literally be the case that God withdraws himself absolutely, metaphysically speaking, such that the created things he withdraws from continue to exist in a state wholly vacated by God. Not even hell – whatever that is – can be construed as so absolute an absence of God. For nothing created has created itself, nor can it sustain its own existence. Creation remains, at every level of its being, inseparable from God who is creatively present actively sustaining it and knowing what he sustains.

• Consider too that God isn’t a ‘composite’ being, i.e., he isn’t composed or assembled from parts more fundamental to him than his actual triune life. He isn’t the achievement or product of a series of divine events which combine over time to produce God’s triune fullness as its effect. “All that God is” is “everywhere God is,” and that’s everywhere without conceivable exception. God is fully all he is everywhere he is, and that means immeasurable and inseparable intimacy with and love for created things. Any notion of divine withdrawal has to be understood as a kind of presence to things as the most intimate act of their being, even when we suffer, even as we do the evil we do. Divine withdrawal, properly understood, is a ‘mode of presence’ not of ‘absence’, a way of being with and sustaining us, not a way of being without us or moving away from us.

• The Cross cannot, then, be understood as contradicting this fundamental sense in which God is fully present, always and everywhere, creatively at work in sustaining and loving the world. Everything God does, including dying, reveals this much to faith. The Cross manifests God’s triune fullness within every narrative of divine withdrawal (even biblical ones). However, the Cross itself is not a narrative of withdrawal. It is a narrative of approach, of nearness, of presence. It is where God, in the full simplicity of triune love, insists upon being with us, thus judging (viz., rendering) all narratives of divine withdrawal, from within the circumstances that created those narratives, to be myths and fabrications of despair and dereliction. The real ‘cry of dereliction’ (as theologians have named it) is not that cry Jesus utters on the Cross (“My God, My God! Why?”). On the contrary, the real cry of dereliction is ours: “Crucify him!” There is the only despair and dereliction connected to the Cross, the dereliction that hangs Jesus on it, while the only real sanity in view is Jesus’ confidence in the Father’s love. The dereliction is heard in a thousand other cries – cries that give up altogether, but also cries that scream their despair all the louder. Much of our despairing dereliction gets published as Christian theology.

• To speak of God ‘witdrawing, then, is to describe the suffering and despair of a life that refuses to embrace the truth of God’s presence. But that refusal does not thereby affirm some other truth – namely, a truth of divine absence. It is rather the pain of our taking the myth of divine absence to be true. But happily God needn’t suffer the pain of falsely believing such a myth in order to free us from it.

I think you are on to some very important theological truths here, argued very cogently, persuasively, and in theologically speaking helpfully. You may want to carefully edit the post to clarify further what you mean.

LikeLike

Oh, I wish I could have edited my comment.

LikeLike

Thanks! I’ve tweaked it several times, trying to tighten it up. But I agree – each point can be expanded into a separate post.

LikeLike

Hi Tom,

I was wondering if you could comment on how your second bullet point intersects with the status of evil within creation.

It’s tempting for me to view evil as a kind of ‘space’ where God is not, like a hole in fabric of creation.

LikeLike

Hi Matthew,

The traditional Christian view of ‘evil’ is that it is ‘non-substantial’ – i.e., it isn’t a ‘being’ or ‘substance’ of some kind, like human beings are one kind of being, amoebas are another, quantum particles are another, and “evil” is another kind of being.

That’s how a lot of us think of evil, i.e., as having its own form and reality within creation. This is different that the traditional orthodox view of evil as ‘privatio boni’ (a ‘privation of being’). It’s very much like defining ‘darkness’. Does darkness really have its own ‘positive’ form or power or do we define it merely in terms of the absence of light? I appreciate the traditional view that understands evil along those lines – as a privation of being, a thing’s ‘failing’ to be the thing it was called to be.

Evil is parasitic. It can only ‘be’ in the sense that the good things God created ‘fail to be’ all God calls and empowers them to be. That kind of parasitic, privative failure doesn’t really occupy space within the ‘real’, substantial world, doesn’t contribute itself meaningfully to defining reality as ‘that which is’. Essentially, your ‘failure to be’ (what God gives you grace to be) isn’t what you ‘are’ – it’s what you ‘are not’.

So my second point had to do with the sense in which God is present (creatively, sustaining us and our possibilities to become all he invites us to) when we are evil. Even if I choose to negate some possibility of being which God offers me, I can never be exhaustively ‘privated’ without remainder. If I exist at all, God must be present giving and sustaining my existence. So he’s on the scence. And the act by which he gives and sustains me in existence is the first and most intimate act of my being. I don’t even contribute to it (because I don’t create or sustain myself). That’s all ‘gift’.

So evil doesn’t ‘create a space’ where things go to be ‘real’ and to ‘exist’ severed from God in some absolute sense. Evil doesn’t ‘create’ anything at all; it only ‘decreates’ things.

Tom

LikeLike

I don’t know your faith affiliation, Matthew, but fewer Evangelicals believe that God is all-present relative to creation. Many are more interested in explaining evil by evacuating God from the scene of every crime (as if we can’t exercise our freedom to do wrong if God is too close) than we are in finding healing through discovering that we are inseparable from God, that we “live and move and have our being in him.” Perhaps this is because folks are uncomfortable with the idea of God’s being fully present wherever unspeakable evil is occurring. In the end it’s a demonic thought, in as much as the absence of God and his exile from creation comprise the narrative in which evil begins and ends.

God help us all.

LikeLike

Hi Tom,

Thanks for the responses. I guess that my problem of trying to conceive of what evil really ‘is’ may come down to stretching metaphors too far. I will think “if evil is a shadow and God is light, then where evil is, God is not.” This makes me tend to gravitate towards conceptualizing evil as a sort of ‘being-vacuum’ or something, but this strikes me as a bit naïve or simplistic. Also, I have yet to properly grasp what exactly is meant by a privation of a good as opposed to merely an absence of a good.

As to my faith affiliation, I would have to say that I don’t really have one. I was raised as a fundamentalist and spent a few years wandering through various evangelical churches, but at this point all I can really say is that my beliefs, sensibilities, and intuitions are at best an awkward fit with that community now. I’ve been shaped quite a bit recently by interactions with eastern orthodox Christians and catholics. I just don’t know quite where I fit in. A lot of what I’m trying to do these days is spot where my conflicting influences have created views that don’t really mesh properly. My understanding of evil is one of those cases where my thoughts feel poorly connected. I have so much floating around in my subconscious. I recall hearing an evangelical preacher say that evil has eternal anti-god power, which now seems somewhat preposterous, but yet ideas like that are still tangled up with other things in my head.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad you came on to ask questions. I completely appreciate your journey and where you’re coming from.

“…what exactly is meant by a privation of a good as opposed to merely an absence of a good.”

“Absence” is as good as “privation.”

But “absence” begs some reference from which it derives its meaning. An absolute metaphysical absence is a meaningless notion.

So long as by absence we don’t mean evil has its own substantial existence and identity, that’s what we mean by ‘privation’ too. Think of something ‘parasitic’ like cancer. It’s more a failure of cells to function as they ought; they use their inherent capacity for life to self-destruct. And a cancerous body exists only as because there are yet healthy cells doing the living. But if all cells were cancerous, we’d call that a dead body, because ‘cancer’ (being privation, or a certain absence or failure of cells to function properly) doesn’t ‘live’ per se.

LikeLike

So if I’m following correctly here, evil is not absence full stop. It is the absence of a good that a thing requires in order to fully and properly be that thing. In other words, it would not be entirely proper to conceptualize evil as a hole in the fabric of what God has made, or a shadow where God’s light does not shine. An absence of something does not imply a gap in what is.

If I commit some evil, lets say by lusting after a woman, I have not thereby created a place where God isn’t, but have perverted the use of an otherwise good faculty. Or as another example, a man without arms is experiencing the evil of ‘armlessness’, but it’s not as though there is a hole in the man’s being that is in need filling. Even thinking of evil as a hole or a shadow may give it too much credit in that it would then at least have dimension (in the analogies) though no substance.

The reason why I felt that there must be a distinction between absence and privation is that it seemed like the idea of privation adds something to that of absence. That I don’t have the good of echolocation like a bat does, is not to say that my lack is a privation. Or that a human fetus at 3 weeks old does not have eyes yet, doesn’t seem like an evil.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Matthew,

Great questions and comments. Thanks for pursuing this.

“Absence” in the sense of absolute nothing is a problem. Absolute nothingness isn’t a certain kind of something. ‘Shadows’ – yeah, that could work, because shadows betoken the realities that cast those shadows, i.e., shadows aren’t ‘substances’ like the realities that cast shadows.

Matthew: If I commit some evil, lets say by lusting after a woman, I have not thereby created a place where God isn’t, but have perverted the use of an otherwise good faculty. Or as another example, a man without arms is experiencing the evil of ‘armlessness’, but it’s not as though there is a hole in the man’s being that is in need filling. Even thinking of evil as a hole or a shadow may give it too much credit in that it would then at least have dimension (in the analogies) though no substance.

Tom: That’s the traditional sense of evil as ‘privation of the good’, right. To say evil isn’t ‘real’ is *not* to say we don’t have real experiences that really fail to be all God intends and so really suffer real pain. It means the evil we suffer isn’t an experience of some ‘entity’ or ‘substance’ out there which we give the name “evil” to and which attacks us and hurts us. What’s James say? Each of us sins when he’s tempted by dynamics (desires, attractions, etc.) that define us substantially. So evil isn’t a “relation” in the proper sense. It’s more a “misrelation.”

Matthew: The reason why I felt that there must be a distinction between absence and privation is that it seemed like the idea of privation adds something to that of absence. That I don’t have the good of echolocation like a bat does, is not to say that my lack is a privation. Or that a human fetus at 3 weeks old does not have eyes yet, doesn’t seem like an evil.

Tom: Exactly. “Not to possess” a certain attribute isn’t by itself a privation. For the purposes of describing evil, ‘absence’ means not possessing that good which it is in one’s nature to possess. I like the word ‘telos’ (end/purpose) here. Teleologically speaking, a thing’s God-given ‘nature’ has a unique scope of possibilities to ‘possess’ which are that thing’s end/telos. For me not to possess or instantiate possibilities that are definitive of a nature not my own is not privation of me. It’s when I fail to realize aspects of my own natural possibilities that we’re talking absence as privation.

Tom

LikeLike

Sorry, it’s been a while since I last checked in. Thanks for the reply. I have a couple more follow up questions.

Tom: … To say evil isn’t ‘real’ is *not* to say we don’t have real experiences that really fail to be all God intends and so really suffer real pain. It means the evil we suffer isn’t an experience of some ‘entity’ or ‘substance’ out there which we give the name “evil” to and which attacks us and hurts us.

…

“Not to possess” a certain attribute isn’t by itself a privation. For the purposes of describing evil, ‘absence’ means not possessing that good which it is in one’s nature to possess. I like the word ‘telos’ (end/purpose) here. Teleologically speaking, a thing’s God-given ‘nature’ has a unique scope of possibilities to ‘possess’ which are that thing’s end/telos.

Matthew: One part of this that I struggle to conceptualize within this framework is suffering itself. Assuming that it is correct to say that suffering involves the experience of evil, then it seems that we’re drawing a distinction between evil per se and how it affects us. But suffering qua suffering strikes me as an evil because I cannot imagine that pain would be part of the God-given telos of any creature. The issue is that I don’t know how to conceptualize an experience in a privative way since experiences seem to always have positive content. It feels awkward to try to distinguish further between suffering and the experience of suffering. After all, what is suffering but an experience?

My other follow-up question has to do with sins committed entirely within a person. If I were to form the intention to murder my brother, then I would have already sinned even if I never ended up harming him. Since I have not actually done anything to my brother, what would you say is the evil that has been brought about? I have a few ideas, but don’t want to ramble.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Matthew: …it seems that we’re drawing a distinction between evil per se and how it affects us. But suffering qua suffering strikes me as an evil because I cannot imagine that pain would be part of the God-given telos of any creature.

Tom: I can’t imagine ‘pain’ being a God-given ‘telos’, but I can imagine pain being a necessary part of a God-given ‘process’ toward the fulfillment of a final telos. In fact, I think it’s impossible to imagine the history of human evolution/becoming without a positive function/role for pain as such. Stick your hand in fire, you feel pain. That’s an instructive and positive thing. You eat a bit of a plant that’s toxic and get a severe stomach ache and vomit. There’s a helpful utility there. You try to lift a rock that’s too heavy and suffer a sore back – same thing. Pain can instruct and alert us in ways that secure our survival if we’re attentive. And the pain doesn’t have only to be physical or have a material cause. One can be without others and suffer the psychological pain of loneliness and thus come to know/learn the importance and value of others.

So I don’t find ‘pain’ or ‘suffering’ as such to be convertible with ‘privation’ in the moral sense of ‘evil’. To conceptualize it, think of the Genesis creation narratives where it is said prior to the fall that “it is not good” (a “not good” before the Fall!) for Adam to be alone. That this isn’t a literal historical timeline is fine. It’s the theological/existential priority embodied in a human experience that is “not good” though it is not “evil” either. There’s nothing evil about pain teaching us not to put our limbs into fire, etc. It’s just the limitations of embodied finitude.

Matthew: The issue is that I don’t know how to conceptualize an experience in a privative way since experiences seem to always have positive content. It feels awkward to try to distinguish further between suffering and the experience of suffering. After all, what is suffering but an experience?

Tom: Just so you know – I do not think (with the Orthodox, apparently) that ‘mortality’ per se is the consequence of a moral “fall” into sin. I think God created us mortal from the get-go and that this mortality defines us in our finitude this side of our achieving final immortality as our telos. I don’t take mortality as an ‘evil’ consequence of humanity’s sinfulness per se. Early human beings might slip on wet rocks and crack their skulls open and die, or fall into rivers and drown. I don’t think those are per se evil. I think they’re (or at least they can be) a necessary part of the context we require in which to resolve ourselves freely and responsibly relative to transcendental goods (truth, beauty, goodness, etc.). It’s important for me, then, not to think that the limitations of finitude constitute an evil if those limitations are definitive of a condition necessary to human becoming toward final perfection in Christ.

Matthew: My other follow-up question has to do with sins committed entirely within a person. If I were to form the intention to murder my brother, then I would have already sinned even if I never ended up harming him. Since I have not actually done anything to my brother, what would you say is the evil that has been brought about? I have a few ideas, but don’t want to ramble.

Tom: The evil brought about is your failure to achieve that loving mode of being which it is your nature and telos to enjoy and perfect. To will harm to another is to do harm to one’s self even if one never does to the other the harm one imagines.

LikeLike

Matthew, if you see this, can you email me? tomgbelt@gmail.com. I’ll leave this up for a few days.

LikeLike

Just sent you an e-mail.

LikeLike

[…] Zeus, the group of theologians who wish to prioritize Greek metaphysics over special revelation such as […]

LikeLike

It’s just a ping, but in case you check by in…

Good to hear from ya, Rod. Hope you’re well.

Belief in Zeus as depicted in Greek mythology (a deity every bit as passible as human beings prone to being led about by their emotions) was actually rejected by the Greek philosophers you think Dwayne and I are beholden to. So your “Team Zeus” would be a better label for divine passibilists like yourself since that view has more in common than we do with belief in Zeus.

As for God’s illimitable joy/delight, I can’t think of a single ancient Greek philosopher who believed in it. I get my own views on the matter from the Bible.

As for whether or not God genuinely abandoned Jesus on the Cross, I get my view that the Father did not forsake Jesus from Jesus himself who said (Jn 16.31-33) that though others would forsake and abandon him, he would “not be alone” for his Father would be with him, as well as from other NT sources like the writer to the Hebrews who assures us that Christ endured the Cross purposefully, i.e., sustained by the “joy set before him” – an unintelligible motivation for enduring the Cross (as Hebrews claims he does) if it’s the case that Jesus believed himself cursed by God. No one absolutely forsaken in one’s darkest imaginable hour by the God of all hope is in position to “set before him[self]” a joy that only God can give. In the end, Christ promised (Jn 16) that how God would be with him in his suffering is how God would be with us in ours – unfortunately not a promise you can (or care to) offer people.

If you don’t agree with any of this, that’s fine. If you think hurting people aren’t helped by it, that’s fine. But to say I get these views from ancient Greek philosophy you identify with belief in Zeus is rather ignorant.

Take care,

Tom

LikeLike

Reblogged this on An Open Orthodoxy and commented:

Recent conversations bring me back to this truth: The scandal of the Cross is that it is “not a narrative of withdrawal” that so many make it out to be. “It is a narrative of approach, of nearness, of presence. It is where God, in the full simplicity of triune love, insists upon being with us, thus judging (viz., rendering) all narratives of divine withdrawal, from within the circumstances that create those narratives, to be myths and fabrications of despair and dereliction. The real ‘cry of dereliction’ (as theologians have named it) is not that cry Jesus utters on the Cross (“My God, My God! Why?”); the real cry of dereliction is ours: “Crucify him!” There is the only despair and dereliction connected to the Cross, the dereliction that hangs Jesus on it. The only real sanity in view is Jesus’ confidence in the Father’s love. The dereliction is heard in a thousand other cries – cries that give up altogether, but also cries that scream their despair all the louder. Much of our despairing dereliction gets published as Christian theology.”

LikeLike