I will end this post with the suggestion that what Christians call the inspiration of Scripture is just the presence of final causality at work in Israel’s history. But I want to explain this thought on the heels of a few reflections.

I will end this post with the suggestion that what Christians call the inspiration of Scripture is just the presence of final causality at work in Israel’s history. But I want to explain this thought on the heels of a few reflections.

Some suggest the “dialectical” nature of inspiration which recognizes the conversational nature of Scripture. This involves particular assumptions about how God is inspirationally present in the conversation between God and humanity which Scripture purports to be. In what sense does inspiration embrace human contributions that ‘get God wrong’? Does saying the Bible may get it wrong mean such texts do not reveal God? Greg Boyd, to pick a recent example, parses out the dialectical nature of Scripture by distinguishing between a text’s “surface” (the explicit, intended claims of its authors/editors) and its “depths.” If a text gets God wrong, it does so on its surface. These same texts, however, possess a “depth” which is brought to light by faith reading the texts in light of the Cross. Greg explores this at length in CWG.

I’m unsure, though, how Greg understands “surface” and “depth” to relate to one another in the composing of texts. Are surface and depth each a feature of the OT texts themselves, or are the “depths” a separate text, as it were, composed as the Church reads the OT Christologically? The latter tends toward what Greg objects to as a “dismissive” approach to the violent texts, not very different from simply denying that these texts are inspired. Greg, I believe, wants to take the additional step in making the Christological “depths” of OT violence texts a compositional feature of those texts. Why? Because Jesus took those violent texts to be inspired (in their textual form and claims), and we shouldn’t think that Christ was mistaken in this belief. This would be in contrast to a view that identified inspiration with the light of the Cross cast upon the surface of texts enabling us to perceive in the shadows cast the extent to which texts fail to portray the cruciform shape of God’s character and intentions. One may ask how this is any different than reading the Vedas, the Quran, or The Pearl of Great Price Christologically.

I occupy a place somewhere in the middle, I think. I do not want to dismiss OT texts that “get God wrong” as so much uninspired paganism to be cast out of the canon of Scripture. I do value these texts and I think together they constitute an inspired space where we encounter the voice of God. But I also recognize that I’m only able to value these texts this way through and because I read from from the perspective of their end in Christ’s life and mission. I’ve tried to work through this in my What is the Bible? series. Permit me a quote from Part 1 of the series:

We imagine the human authors of Scripture inspired by God in much the same sense that God inspires anybody — through the prevenient grace of his presence working in cooperation with what is present on the human side of the equation. Hence, inspiration achieves greater or lesser approximations to the truth as it works with and through the beliefs and limitations of authors.

What makes the Bible unique as God’s word, then, is not the manner or mode of inspiration (which we think should be understood as typical of divine inspiration universally), but the subject matter with which God is concerned. It is the ‘what’ and not the ‘how’ which makes the Bible unique, i.e., the content and its purpose which in the case of Scripture make what is otherwise the standard mode of God inspiring human thought to achieve something unique and unrepeatable. Biblical inspiration, we might say, is unrepeatable because this history, this context, this pursuit of this purpose (incarnation) are all unrepeatable and not because God inspires humans ‘here’ in some unique and unrepeatable way…

Might some errors belonging to these persons find their way into the text? Yes. No human author possesses an inerrant set of beliefs. No one person’s transformation and world-construction is complete or error-free. But overtime, enough of the truth needing to be said gets said in enough ways that a worldview is formed adequate for the Incarnate One. This means we view inspiration as relative in the first sense to preparing a context adequate for incarnation and not primarily about providing us a philosophical or scientific textbook with inerrant answers to whatever questions we might put to it.

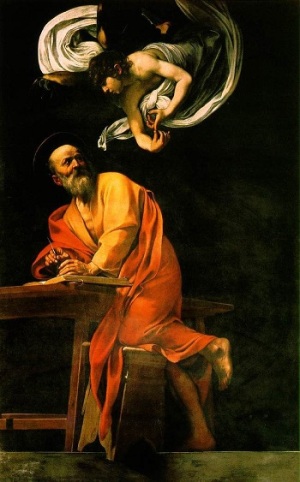

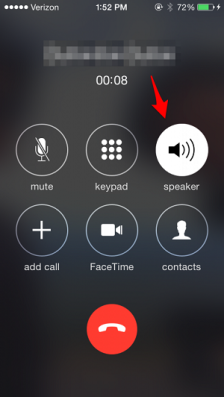

What I’d like to add here is an analogy to help expresses how we might imagine the dialectical nature of God’s inspiring presence in Scripture – both in the composing of texts and in reading them Christologically. We ask students to imagine reading the Bible in terms of listening to one end of a telephone conversation. We read Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, for example, and find ourselves on one end of Paul’s conversation with the Corinthians.

Often what a person says on the phone can only finally be understood in the context of the whole conversation. Those of us listening to one side have to construct a picture of the whole conversation as best we can. Reading the Bible is a bit like that. Its texts are dialectical. When we read 1Corinthians, we have to reconstruct the relationship between Paul and the Corinthians based only on what we hear Paul say (never mind the fact that we ourselves are conversation partners who bring our own contributions to interpreting the half of the conversation we possess).

Widen this analogy a bit and imagine the Bible in its entirety to be one side of a conversation Israel and God are having. When we read the Bible, we are listening to one side of that conversation. Right here we immediately meet a fundamental question about the Bible. When the Bible records, “Thus says the Lord,” aren’t we listening to the divine side of the conversation? Isn’t the Bible essentially on “speakerphone” so that at one moment we’re directly hearing the human side of the conversation (a prophet or king) and at the next moment hearing God?

Widen this analogy a bit and imagine the Bible in its entirety to be one side of a conversation Israel and God are having. When we read the Bible, we are listening to one side of that conversation. Right here we immediately meet a fundamental question about the Bible. When the Bible records, “Thus says the Lord,” aren’t we listening to the divine side of the conversation? Isn’t the Bible essentially on “speakerphone” so that at one moment we’re directly hearing the human side of the conversation (a prophet or king) and at the next moment hearing God?

I apologize if you’re hearing it first from me, but the answer is ‘no’, that’s not what’s going on. Divine inspiration, whatever it is, does not give us God’s side of the conversation unmediated by the instrumentation of human voices. If or when we hear God’s voice in Scripture, we hear it in their voices. Thus, “And God said” means “And Israel [or some prophet or other] said ‘God said’.” We are listening to Israel’s side of her conversation – hearing Israel speak, repeat what she thinks God is saying, disagree with other Israelites about what God is saying, cry, scream, interpret and misinterpret. All this comprises the “surface” of the text (Israel’s side of the conversation), and it’s all we have.

That’s not bad news. We have every reason to believe that Israel could and did hear God through prophets and others. But sometimes – and here some will become uncomfortable – we have good reason to suspect Israel did not hear God rightly but that she monopolized the conversation to promote her own agenda. The good news is that when it comes to a text’s portrayal of God, the Christian reader has in Christ a way to adjudicate the OT conversation. But why think Jesus gets God right? We think Christ faithfully embodies the drama of divine-human conversation because God raised him from the dead – and not for any other reason.

We have, in Christ then, a truthful revelation of the conversation between God and Israel. It is this conversation that brings the entirety of Israel’s recorded conversation to light – to the light of confirmation and to the light of judgment – confirmation because God can be seen to be faithfully carving out on the human side of the conversation (Israel) truth sufficient for Incarnation (where God will assume the human side of this conversation) and judgment because now through Christ we’re able to distinguish where and how human authors get God wrong.

To return to Boyd. Once we admit this much, I’m not sure how exactly to locate in the disfigured “surface” of texts an inspiration by which God renders that surface the means of accessing a “depth” which faithfully reveals God (as Boyd seems to argue). Functionally speaking, once Christ’s voice becomes the means by which we listen to the entire conversation we call Scripture, inspiration is reduced to Christ who defines the hermeneutical center, and when you’re standing at the center relating to things in terms of their relationship to that center, it doesn’t really matter how close or distant things are from the center.

This is a real problem for inerrantists who want every explicit claim of the text to be the center. Every “surface” has to be its own “depth.” But if God is truly transcendent, and all things tend toward their final end in Christ, and God unites himself in covenant to Israel to carve out space for his own Incarnation – then we’re free to let the Bible be the mixed-bag that it is. I suggested previously:

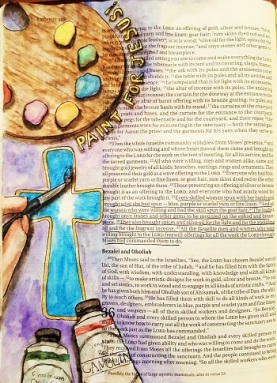

We prefer that every part of the Bible [on its “surface”] be a perfect, inerrant conclusion to some aspect of the human struggle and journey. Girard’s phrase [“texts in travail”] suggests that the Bible itself is that journey. The texts of Scripture are Israel in process, in travail, trying to figure the world out. At times Israel lunges forward with the profoundest of insights, while at other times she conscripts God into the service of her own religious violence and apostate nationalism. Sometimes she gets it right. Other times she gets it horribly wrong. The texts we call the Old Testament are not just neutral, third part records of observations of events. They are one of the events. They participate in and constitute Israel’s up and down journey of faith. They lay bare the heart and soul of the human journey in its best and worst. They are “texts in travail.”

All that said, let me bring back the suggested axiom I opened with. I’ll probably hack this up fairly well, so be patient. Don’t laugh too loudly. This is tentative and speculative.

I’m suggesting that when it comes to understanding God’s inspiration of the Bible:

- Inspiration is the presence of final causation.

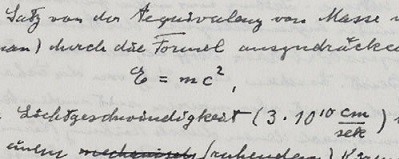

We can express this as a formula. A what? Yes, a formula.

As I pondered how a God of constant truth would give us a book whose portrayals of God are only relatively accurate, I found myself back and forth between this ‘constancy’ and ‘relativity’. Now, don’t laugh too loudly, but Einstein’s E=mc2 came to mind. The relativistic mass (m) of a body times the (constant) speed of light squared (c2) is equal to the energy (E) of that body. Notice the presence of both a relativistic factor (the mass of a body) and a constant (the speed of light). I’m not transposing this into a theological axiom. It’s just an analogy that got me thinking. But for those of you who love logical notation, we can express the dialectical nature of the inspiration of biblical texts as:

I=tc2

The biblical text (t), relative in the extent to which it approximates the truth (that is, all texts are relative), times (the constant of) final causality squared (c2) expresses the divine inspiration (I) present in/as the text.

What the heck?

Start with the constant, final causality (c). By final causality I mean God as the final end of all things. I’m not thinking of Greek philosophical arguments here. I’m contemplating Christ as the ‘telos’ or ‘end’ (of the Law, Rm 10.4, and of all things created “through and for” Christ, Col 1.15-20). I’m thinking especially of the risen-crucified Christ as in himself embodying the telos or fulfillment of creation. I’ve previously suggested that the Bible be understood in the context of Incarnation being the means of achieving God’s unitive purposes for creation, and this context makes it relatively easy to understand the inspiration of texts:

Our first suggestion is to place the incarnation at the center of one’s understanding of God’s unitive purposes for creation and view Scripture as subservient to these ends. If God is to incarnate and as an individual develop his sense of a unique identity and mission, he needs to be born into a cultural-historical-religious context sufficiently truthful to inform that development. No one develops an understanding of who they are and what their destiny is apart from these contexts. So the question of a context sufficient to shape the Incarnate Word’s embodied worldview and self-understanding is paramount, and in our view that is what Scripture is primarily about. The Word could not have been born randomly into a culture which was not an adequate means of identity formation. Creation is the context for incarnation to begin with, yes, but beyond that the construction of a suitable context for identity formation is what God’s choice of Abraham and Israel is fundamentally about. All else extends by implication from this single purpose.

By ‘final causation’ (c), then, I mean the final union of creation with God in Christ, the conformity of all things to the character and intentions of Christ. I view inspiration teleologically, not just in the sense that OT narratives anticipate their fulfillment in NT realities (a kind of rhetorical teleology that any inerrantist would affirm). I mean something that demonstrates the ability of a transcendent final end to be present to and in every religious aspiration, even when they miss the mark (a compositional teleology, something no inerrantist would agree to). Previously here:

In a word, [Scripture] must be sufficient as a means to the rightly perceived ends for which Christ self-identifies and suffers as the ground for Christian discipleship and character transformation. Much of our modern problems surrounding the question of inerrancy stems from our desire that the Bible be much more than this…

In a word, [Scripture] must be sufficient as a means to the rightly perceived ends for which Christ self-identifies and suffers as the ground for Christian discipleship and character transformation. Much of our modern problems surrounding the question of inerrancy stems from our desire that the Bible be much more than this…

Scripture’s…function is understood first to be the securing of a worldview adequate for the development of the Word’s incarnate self-understanding (identity and mission) and then secondly as a means for character formation into Christlikeness…

In the necessary respects we require, Scripture’s truth is self-authenticating to faith. That is, where its narrative is believed [with a view to Christlikeness], it either proves itself truthful in all the ways we require (i.e., it saves, it heals, it transforms and perfects us) or it does not. This is where Scripture functions inerrantly in us relative to our identification with Christ. Personal transformation into Christlikeness is the purpose and proof of the only inspiration we should concern ourselves with.

Why is final causality squared (c2)? It is squared to represent the function of final causes in both opening creation up to the future and, interpretively, clarifying the past. The Spirit of God is present in the authors of OT Scripture orienting and opening them both toward the future (toward some realization of the truth) and then, realized in Christ, toward the past to explain, judge, and confirm the history of Israel’s own conversation. Final causation is squared as an expression of its presence both in texts prompting and calling them forward and, in Christ (the final cause/end embodied), judging and calling texts to account. As final end, God both opens texts to the future as they are composed (dialectically) and closes the question of their truth value as they are read in light of the fulfilled embodiment of that final end – Christ. This is the way I understand inspiration (I) to be fully present at work in the composition of texts (which I think Greg will appreciate) and also present in the Christological reading of those same texts.

Hi Tom,

Let me say thanks for that and that I agree with all that you have said above.

But, can I ask you, what do we do with the WORDS OF JUDGEMENT, VENGEANCE AND VIOLENCE OF GOD (excuse the caps) that Jesus is reported to have said?

This is THE issue with the Jesus lens.

I’ve tried to communicate with Brian Zahnd about this since SITHOALG but have heard nothing back.

What say you?

Blessings.

LikeLike

Lewis,

I think at some point we have to say what violence is. What makes a thought or word or deed ‘violent’? I have a very specific answer to that:

I did try (in a conversation that included Greg Boyd and other fairly well-known people who were reviewing Greg’s book) to get others to define violence. There was some reluctance to even attempt it. But for those who tried, no broad agreement was reached. Greg didn’t wanna offer a definition.

But the whole effort to establish God as non-violent collapses into a consuming ambiguity without a clear understanding of what constitutes violence. If you won’t define violence, what are you even saying when you say God is “non-violent”? And if we can’t together say what violence is, we can’t together mean the same thing when we say God is non-violent. Greg said he removed a section defining violence from the book because in the end he thought genocide is so obviously ‘violent’ and ‘evil’ that there’s no need to prosecute the violence of it. That’s genoicde. Fine. What about other less obvious forms? What about Ananias and Sapphira (Acts 5)?

This came up listening to a QandA session at Woodland Hills Church with Greg and Bruxy Cavey. Greg was explaining why his non-violent view of God meant that God had nothing to do with the deaths of Ananias and Sapphira. Bruxy Cavey (a passionate defender of the “non-violent” love of God) disagreed. Greg was surprised. Greg said it was Peter who used his “irrevocable God-given spiritual powers” to murder them. Bruxy said he thought it was God who “took Ananias and Sapphira out” of the equation and that this was in God’s perspective a right, wise, and loving thing to do given the wider circumstances.

The point is that Bruxy and Greg are equally committed to ascribing zero violence to God. But the only reason Bruxy can see God’s taking Ananias and Sapphira out of the equation as wise and loving and Greg see is as violent is because the two of them define ‘violence’ differently. On Greg’s view, Bruxy can’t really be an advocate for the non-violence of God’s love. The difference between them won’t show up in genocidal passages (because everybody agrees that genocide is evil), but it does show up in other controversial passages (like Ananias and Sapphira) that are central to Greg’s thesis but where other non-violent advocates disagree with Greg.

I take Acts 5 as unproblematic because, with Bruxy, I don’t view what God does as “violent.” Greg does. And I take Jesus’ pronouncements of judgement for the wicked in the same sense. It is no violence for the wicked to suffer the pain of excluding God from their life. Pain is what you’re left with. And pain – even inflicting pain – isn’t necessarily “violence.” Some pain can be remedial.

Tom

LikeLike

Hi Tom,

Jesus seems to predict a particular time of judgement where certain people will begin to experience suffering more than they did before this point.

We might not consider this as violence committed by God but at the least it suggests that God intervenes (or stops intervening to prevent this) allowing the experience of increased suffering.

Either way it suggests God creating a time for them to reap what they sowed

If this is the case, surely this can only be if there can (will) be redemption later, this judgement, then, serving to awaken them to their error.

What do you think?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tom, when you get a chance I’d love your take on these three questions. https://notesonthefoothills.wordpress.com/2017/10/19/three-conundrums-for-open-theism/

LikeLike

I typed out a lengthy, detailed response and posted it to the comments section there. Now I don’t see it. And I didn’t save what I wrote. :o(

LikeLike

damn

LikeLike

It’s in my head. I’ll write it up.

LikeLike

Got some thoughts up there. More to come.

LikeLike