Many thanks to Fr Aidan for celebrating our one year birthday here at An Open Orthodoxy with a thoughtful and challenging post. We thought we’d share a few points of agreement and disagreement with Fr Aidan’s comments.

Many thanks to Fr Aidan for celebrating our one year birthday here at An Open Orthodoxy with a thoughtful and challenging post. We thought we’d share a few points of agreement and disagreement with Fr Aidan’s comments.

If you rummage through our posts this past year, you’ll recognize that we’re in total agreement with Fr Aidan that open theists have no real appreciation for divine transcendence. Open theists generally don’t know what to do with transcendence. At best it represents how very much larger than us God is (Fr Aidan’s sky-God precisely), and this is generally just ‘sameness writ large’, not transcendence. Fr Aidan is totally on point here. A few published open theists (two or three we can think of) have ventured to speak of God’s transcendence in a more traditional sense. The most serious engagement is — no surprise here — Greg Boyd’s PhD work on Hartshorne (Trinity & Process) which we’ve discussed here as well. So Fr Aidan hit the nail on the head: open theists generally speaking have no real sense of divine transcendence.

A second related point of agreement is CEN (creation ex nihilo), but not CEN vaguely related other core claims; rather, what really is implied about God and creation by CEN. It’s our observation that the most open theists tend to do with CEN is use it to distinguish themselves from process theists by affirming God’s freedom from creation. But we mean the why behind CEN. When explored with more attention, CEN led Dwayne and me to embrace other important traditional features about God. It began with facing the most obvious entailment of CEN, namely, the utter and absolute gratuity of creation (on the one hand) and the utter, absolute and necessary (i.e., transcendent) fullness of God.

It’s precisely here where Dwayne and I would begin to disagree with Fr. Aidan as regards the temporal status of God’s relating to the created order. In spite of there being important ways to qualify terms like ‘experience’ and ‘temporal’ (and even ‘knowing’, ‘perceiving’ and ‘relating’) when used to describe God as creator and sustainer of the temporal world, we’re not convinced that creation is any less gratuitous or God-dependent in those senses worth affirming if God is believed to have (qualifiedly) temporal experiences of the world. In fact, it’s because we affirm God’s freedom from the world that we think God should be conceived of as ‘actually’ free from creation and not merely ‘formally’ or ‘abstractly’ free from the world.

It’s our conviction that the divine actuality (as the plenitude of being, as unimprovable aesthetic satisfaction, as the utterly complete and imperturbable divine relations) is free from creation which encourages us to conclude God is ‘actually’ free from creation, not just free on paper (‘formally’ free, as it were). But in the classical view of God as actus purus, God is never ‘actually’ free from his determination to creation. On the contrary, God actually just is his determination to create and that determination defines him essentially, eternally, etc. (as McCabe shows — there is no God apart from the God who creates), which to us denies that God is free from the determination to create. We think a qualified view of divine temporality can better affirm both the essential divine freedom and triune fullness and creation’s absolute gratuity without historicizing that transcendent fullness by assuming God becomes God in all the objectionable ways process theology (on the one hand) and Jenson and McCormack (on the other) advocate.

For an interesting take on the Fathers view of divine freedom and temporality, see David Bradshaw’s “Divine Freedom: The Greek Fathers and the Modern Debate” in Philosophical Theology and the Christian Tradition: Russian and Western Perspectives, 77-92, and “Time and Eternity in the Greek Fathers,” The Thomist 70 (2006), 311-66. Fr Aidan’s post is a good prod to Dwayne and me to finally get around to arguing that Bradshaw’s understanding of God’s relationship to time doesn’t preclude the sense in which God ought to be viewed as temporal by open theists.

Thanks again Fr Aidan for giving us much to think about. McCabe is on our to-buy list!

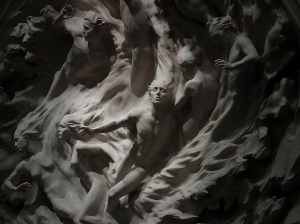

(Frederick Hart’s “Ex Nihilo”; Washington National Cathedral).

Thanks for your kind words, Tom. May your blog prosper!

T: “But in the classical view of God as actus purus, God is not actually free from his determination to creation.”

This is the contested point, as you know. Certainly the Church Fathers and Aquinas did not believe that their understanding of divine eternity entailed a lack of freedom; indeed, they insisted on this freedom.

But it seems to me that an apophatic reserve is in order here: we can no more conceive the eternal God’s relation to created temporality than we can conceive his relation to free human agency. At both points, I suggest, philosophy has reached its limit.

And I suspect we will be talking about this question for a long time! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I definitely wanted to shake God’s hand when I get to heaven and thank him for everything. So I hope he’ll take a break from transcendence long enough to accommodate me! 😛

LikeLiked by 1 person

Will an apophatic hand-shake be sufficient for you? 😉

LikeLike

I can’t say!

LikeLike

Fr. Kimel: “Certainly the Church Fathers and Aquinas did not believe that their understanding of divine eternity entailed a lack of freedom; indeed, they insisted on this freedom.”

Of course, their having *believed* in both divine freedom and actus purus, etc., implies nothing regarding the doctrines’ joint consistency. 🙂

I think Tom’s basic point could be put at follows: If God just *is* (is identical to) His will and if (as is clearly the case) God wills that there be a creation, then it follows that creating is *essential* to God. Moreover, if, as the Thomistic doctrine of divine simplicity would have it, God’s will just *is* (is identical to) His knowledge, then since His knowledge encompasses all of creation, so too does His will. And if the latter is essential to God, then so is the former. Hence, God is not only not free with respect to there being a creation, He is not free with respect to *any* aspect of creation.

Appeals to apophaticism or divine mystery are irrelevant in this context, for it’s not something we *don’t* understand that creates the difficulty, but rather something we *do* understand very well, namely, the indiscernibility of identicals.

Let g = God (as God *actually* is)

Let w = God’s will (as it *actually* is)

Let Cx = x is essentially such that there is a creation

1. g = w (assumption: divine simplicity, Thomistic style)

2. Cw (God’s will, as it actually is, is essentially such that there is a creation)

Therefore, (by the indiscernibility of identicals)

3. Cg (God, as God actually is, is essentially such that there is a creation)

Notes:

(2) is true because if there had been no creation, then w, God’s will as it *actually* is, would not exist. Rather, a different divine will w* would exist instead.

(3) follows from (1) and (2) for the same reason that from “2+2 = 4” and “2+2 is essentially even” it follows that “4 is essentially even”.

LikeLike

Interesting post! 🙂

LikeLike